| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

the houses opposite of our place |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Trancoso

is situated on a grassy bluff overlooking the ocean and miles of fantastic

beaches. The village belongs to the prefeitura of Porto Seguro, a historical

small town on Brazil's northeastern coast popular both with foreign and

Brazilian tourists. Trancoso's central square, known as quadrado,

is lined with small, colorful colonial buildings and casual bars and restaurants

nestling under shady trees. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The history

of Porto Seguro, which means 'safe port' in Portuguese, and actually of

the whole of Brazil, begins on April 22, 1500, when Pedro Álvares

Cabral's squadron saw from a distance a rounded elevation - Monte Pascoal,

that lies south from Porto Seguro. In search for a safe place to moor, the

thirteen caravels sailed along the coast heading north and finally anchored

at a large bay of deep waters, a little before the evening of April 24.

The place was later called Baía Cabrália where presently is

situated the town Santa Cruz Cabrália. When Cabral departed, on May

2, he left two men banished from Portugal whose mission was to learn the

language and customs of the Tupiniquim Indians, besides two sea boys who

deserted to adventure in the luxuriant tropical woods. That was the beginning

of the occupation of the new lands by the white men. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

On November 9th of 1759, the year the Jesuits got kicked out of Brazil,

Trancoso, by royal decree, was elevated from aldeia (village) to

vila (township). At this time the place consisted of 62 houses, 14

of those had shingled roofs. 500 indios living from fishing and the cultivation

of cassava lived in Trancoso. A mid-eighteenth-century list of missions

administered by the Jesuits classifies the inhabitants at Trancoso at that

time as "Tupinikins or Tabajaras mixed with Tupinan" |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

an

aerial view of Trancoso that I found on the web |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Even as

late as 1820, export agriculture had failed to take firm root in Porto Seguro;

despite the growth of production for local markets, the region remained

a poor backwater where settlers still worried about Indian attacks. Settlers,

royal officials, and backwoodsmen in southern Bahia were all too aware that

Indians remained a very real "issue" and that the nearby forests

were not empty, uninhabited space. While settlers counted on the labor of

"tame" Indians who were drafted to clear fields, open roads, and

cut timber, they also had to remain on constant watch for any sign of "wild

heathens," whose raids and attacks could lay waste to a fledgling commercial

economy. |

|

|

| |

|

Efforts

were aimed at a creating a stable and productive Indian peasantry through

a combination of coercion, forced cultural assimilation, and close supervision.

Although unsuccessful over the long run in halting frontier expansion, Indian

resistance did delay and restrict the development of a strong commercial

economy in the region. An appointed white "director" and a scribe

would now be posted in every Indian aldeia and charged with the

tasks of "civilizing" the Indians, removing them from the "dense

darkness of their rustic ways," and encouraging them to practice settled

agriculture. |

|

|

| |

|

Directors

struggled for years to have Indians replace large palhoças

(thatch huts) that sheltered several couples and their children with brick

and tile houses big enough to accommodate a single couple with their children.

The brick and tile houses did, indeed, directly interfere with the daily

lives of Indians by dividing them into family units that met Portuguese

norms and reinforced notions of Christian morality as taught by parish and

missionary priests.

|

|

|

| |

|

When the

German traveler and naturalist Prince Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied visited

the Indian town of Trancoso in 1816, he found it virtually empty: "The

inhabitants live on their farms (roças) and come to church

(and hence into town) only on Sundays and on feast days." |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Wherever

possible, Indians were to be fully "domesticated"- that is, transformed

into a settled peasantry that would contribute to an expanding commercial

economy and uphold Portuguese rule. But, at the same time, "domestication"

would also clear the way for further Portuguese settlement and ultimately

lead to the complete disappearance of Indians as a distinct group within

the region's population. Direct and open resistance to this project only

subjected the Indian population to even greater pressures, culminating,

in the first decades of the nineteenth century, in one of Brazil's last

official Indian wars. |

|

|

| |

|

By 1820

Porto Seguro had grown to reach a total of over 16,000 inhabitants, including

3,650 Indians. In only two of the comarcas (judicial districts) of

Porto Seguro's nine townships, Vila Verde and Trancoso, did Indians still

account for the majority of the population. |

|

|

| |

|

Even in

the mid-nineteenth century, southern Bahia remained a frontier region of

ongoing contact, accommodation, and conflict between settlers and Indians.

As the trade in cassava flour grew, settlers increasingly displaced Indians.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The development

of trade and agriculture accompanied population growth in southern Bahia.

The region emerged in the late eighteenth century as an important supplier

of farinha de mandioca (cassava flour) and salted fish for urban

markets within Brazil. Farinha made by farmers in Porto Seguro

was sold not only in Salvador, the Bahian capital, but also in Rio de Janeiro

and in Pernambuco. Trade in farinha allowed settlers in the region

to acquire larger numbers of imported African slaves and Brazilian-born

slaves of African descent. |

|

|

| |

|

From the

1580s onwards, the importation of Africans to Brazil increased dramatically.

The African slaves brought their ‘macumba’ (voodoo) rites

to Brazil. Even today, the candomblé cult is strong in Bahia.

Though, to my disappointment, such traditions were unknown among the locals

of in Trancoso. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Nearly

five hundred years after Cabral, Indians still live around Monte Pascoal

and on reservations elsewhere in southern Bahia. They continue to struggle

against landowners and loggers in the area to hold on to what little land

they still retain. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

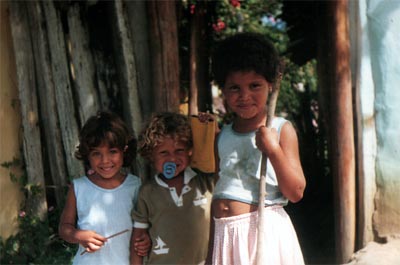

The local population of Trancoso visibly has both Indio and African traits.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Estrela,

João and Duda |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Before

the first dropouts from the cities of southern Brazil settled in Trancoso

in the early seventies, the village, populated mainly by only two extended

families, was virtually cut off from the rest of Brazil. |

|

|

| |

|

It

is said that until the sixties, money wasn't used much in Trancoso, and

goods changed hands by way of barter. A local friend told me that when she

was around the age of eight, two girls with lice-infested hair came to the

village. Before those parasites were unknown in Trancoso. This seems to

me about the most convincing proof that previously there really wasn't much

contact with the rest of the world. To go to Porto Seguro meant a tiresome

journey by horse or donkey. |

|

|

| |

|

Only

in the eighties did Trancoso get electricity and a school. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

When we

arrived in 1984, conditions were still very minimal. The only store, a small

dark room featuring a few wooden shelves, sold rice, beans and two or three

varieties of local vegetables. On demand the store owner also sold a few

medicines, though the good lady wasn't what I'd call knowledgeable as to

their uses and properties. When my neighbor's daughter suffered from a bad

ear infection, her mother bought a bottle of ear drops at the grocers. After

learning about those drops causing the poor girl terrible pain, I asked

to see the bottle. It contained a remedy for athlete's foot. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

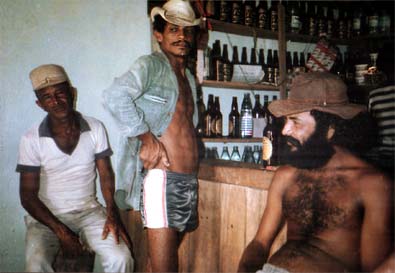

typical

bar on the village square |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

There

were plenty of tiny bars bordering the quadrado where the locals

liked to hang out, play snooker and drink pinga, another name for

cachaça, the local sugarcane booze. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Apart

from the buildings lining the quadrado, Trancoso in the early eighties

consisted of only a few dozen houses. A bit further away, landless people

started to build their homes on occupied grounds, according to a Brazilian

law allowing land not used by its owners for a certain amount of years to

be claimed. This section of Trancoso was called invação,

invaded territory. It consisted of barren, sandy soil, not to be compared

with the fertile earth near the village square. |

|

|

| |

|

Most

of the natives lived in simple mud houses: Neighbors and friends join to

throw as much mud on a framework of wooden stakes as is needed to transform

it into a wall. On completion a party with lots of cachaça is

held, so there usually is no lack of volunteers. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

houses built of stakes and mud |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

As

to the durability of those constructions, I guess it's not too many years.

While still living in the rented place on the quadrado, one evening

while having dinner sitting around the big table out back, we experienced

the sudden collapse of our neighbor's adjoining wall into a heap of rubble.

For the next few weeks we had a live reality show right in our backyard,

as we couldn't help but witness everything that went on in that family's

now open-to-the-world kitchen. It kind of looked like a stage, with the

actors entering and leaving through two door openings. The head of the family

was an uncouth, insensitive fellow, who loved to terrorize his wife and

the boys at any opportunity. His elder son often hid himself in the bushes

out of fear of his father. When the wife was giving birth to another baby

and complications arose, instead of arranging transportation to a hospital,

her husband left her to the attention of some passing tourist. Only much

too late was she brought to a clinic in Eunapolis, with the consequences

of the baby being dead and the mother not able to ever have another one.

When the poor woman returned home a few days later, her vile husband shouted

at her that she was now "castrated" and useless. |

|

|

| |

|

I

was asked to come over and take some pictures of the dead baby. This was

nothing uncommon in South America, nonetheless, I couldn't do it, I was

afraid not to be able to stand the sorry sight, and that I might faint.

Somebody else went and took the snaps, which we had developed and handed

over later. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Trancoso's

historical church |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Trancoso's

church, being one of the oldest in all of Brazil, nonetheless didn't even

feature a regular priest. Once in a while some obese red-haired foreigner

appeared to hold a service and to baptize some newborns. Occationally he

had to baptize some teens from families living a bit farther away, who obviously

had included "gotta have those brats baptized" way down near the

bottom of their priority list. |

|

|

| |

|

When he the padre happened to turn up,

hardly any of the local males attended mass, because their drinking habits

inevitably were part of the sermon. |

|

|

| |

|

I only happened to witness the padre

preaching on one single occasion, and was totally dumbfounded to hear him

tell his congregation that animals have no souls. Exactly

the type of stupid misinformation the villagers needed: They treated animals

very cruelly and loved to hunt down and kill anything that moved. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

In

the eighties, the church was in a sad state of disrepair. The paint was

flaking off and the wood had partly the consistency of a sponge. With things

continuing that way, it was only a matter of time for the church to be reduced

to a heap of rubble. As this became evident to the public, some of the foreigners

and Brazilian dropouts living in Trancoso recruited volunteers and organized

some renovations. For a full day we all were busy painting and hammering

away. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Once

our own house was ready and my garden in bloom I often got accosted with

demands for armfuls of bougainvillea branches to decorate the church with.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

With

the priest only showing up every few months, Jehovah's witnesses entered

into the religious vacuum of Trancoso. Local converts, their blouses buttoned

up to their chins, started to make their rounds on Sundays, knocking at

doors. |

|

|

| |

|

Millions

of Brazilians are crente, as the adherents of Jehovah's witnesses

and other evangelical sects are called. It seems the Brazilian brand of

Catholicism doesn't meet the requirements of the masses anymore. Fatima

told me that meanwhile there are churches of various sects all over Trancoso.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The only

water supply for Trancoso was the nearby river, located at the foot of the

plateau on which the village stands, where an old electrical pump noisily

did its job. Often the pump was broken for days or even weeks. This meant

all the water needed for construction and for the restaurant had to either

be hauled up the steep path from the river by locals employed for that purpose,

or it had to be gotten by jeep in jerrycans. |

|

|

| |

|

As the

water pump wasn't located far from the place the villagers used to wash

their clothes, and themselves as well, I thought it safer to buy a simple

clay water filter for our drinking water. I've often drunk river water and

worse on my travels, nonetheless I didn't want us to imbibe all those shampoo

and soap remnants, though of course I couldn't be sure about the filter

being able to get rid of them. |

|

|

| |

|

Washing machines at that time were about unknown in Trancoso.

All the washing was done at the small river below. As I had neither time

nor much enthusiasm to do our washing, which amounted to quite a lot as

it included bed sheets from the guest rooms as well, I paid Seu

Frederico's wife for the job. Whenever Fatima's friends went down

to the river to wash clothes she went along to help them, but she refused

to take some of our own washing along. The girls loved to frolic and play

around in the water. |

|

|

| |

|

To dry, the wet clothing was extended either on some bushes

or preferably on fences of barbed wire. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

One

of the main attractions of Trancoso is the endless beach, according to Brazilian

Playboy magazine one of Brazil's Top 20. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Trancoso

beach |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

A

great stretch of the beach is owned by some local kingpin and politician.

He hadn't paid for it in money, but rather came into its possession in exchange

for a transistor radio and a set of dentures for its erstwhile owner. At

least that's what local lore tells; it must have happened around the sixties.

I only know for sure that the old owner's descendents were really pissed

off at how their grandfather had gotten cheated. The new owner used to fly

in by chopter, landing right beside Trancoso's church. He often forgot to

pay locals who worked for him, but nobody dared complain. His word in the

right ear got murderers out of jail. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Fatima

on visit to Trancoso in 2002 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

I have

to admit that beaches are not my thing, I'm more at home in a dry desert

climate. In my four years in Trancoso, I may have visited the beach four

or five times. True, I was usually very busy, but actually I never have

liked wet sand and salty water. I leave that to the tourists. |

|

|

| |

|

A

very old, dark skinned neighbor lady once asked me: "Well, in a way

I understand the white people going down to the beach to get some colour.

But what about the black ones, ain't they dark enough already?"

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The

younger generation of locals started to use the beach for recreation as

well, a habit they picked up from their fellow countrymen from places like

Rio, where the beach plays an important part in a carioca's daily

life. In Trancoso, the native women up to my generation only went down to

the shore to catch some small fishes in the backwaters. |

|

|

| |

|

Zilda,

my neighbor and friend, used to go down to the beach for fishes and crabs

occasionally too. One morning she returned all upset: "You don't

believe what happened, I was all alone in a quiet spot, when suddenly

a naked stranger appeared before me. I've never seen another man save

my husband naked, and I want it to stay that way." Later, she pointed

the offender to her sensibilities out to me: It was an architect from

Rio, a customer of my restaurant. |

|

|

| |

|

The local

menfolks would get real angry at nude male tourists, and loved to threaten

them with their machetes. Nude girls were something else, the same valiant

defenders of morals and decency just stood there drooling. |

|

|

| |

|

I knew a chick that sold rather plain sandwiches, filled mainly with raw

beetroot and far too expensive. This girl usually went down to the beach

with a full basket and only a short while later came back up, all her sandwiches

sold. It was a mystery to me why anybody would buy her tasteless stuff at

such a prize. Until somebody told me that she sold them in the buff. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

My

kids loved the beach. Rashid's dream for a time was to become a professional

surfista, a surfer. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|