| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Brazilians

love to party, to celebrate. Throughout the year there are a number of traditional

festas of great importance, all more or less connected to the Church

calendar and involving saints. Each of this festas has its very

own customs, its special rituals and songs. |

|

|

| |

|

Fatima

told me that many of the traditions she grew up with are changing and even

disappearing. Life in Trancoso has changed dramatically due to the influx

of people from all over Brazil, who now greatly influence the social life

of the place. They brought their own customs along and the old ways are

getting forgotten. |

|

|

| |

|

I

am grateful for the help of my daughter, who still remembers the festas

as they used to be in the eighties and helped me with this section. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

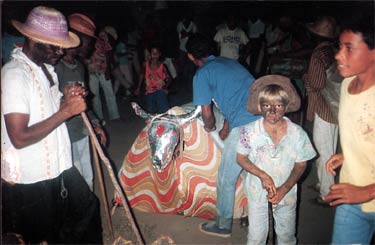

Rashid

at "Bumba meu boi" |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The first

holiday of the year used to be Bumba meu boi, on the day of Epiphany

or Three King's Day. After nightfall, a man in the costume of a boi

(bull), gets driven through the village by a few black-faced guys wielding

sticks, accompanied by the dancing villagers singing the songs belonging

to this holiday. Arriving at the house of the festeiro, the man in

charge of the festivity who has to supply food and drink to the crowd,

the boi lies down and gets "slaughtered", following the

announcement of: "Vamos repartir o boi, pessoal" (let's

divide the bull, folks). Singing amusing verses about every part

of the boi and who's gonna get it, everybody has great fun.

|

|

|

| |

|

All the

while people have to look out for the jaguará, who jumps out

of dark hiding places, attacking them using a dead horse's head to savagely

bite whoever he catches. In older times, the horse's mouth used to be filled

with red hot charcoal, making the bites a lot more painful! |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

procession back in the eighties |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

At

the end of January, the first one of the big saint's holiday, the festa

of São Sebastião, is celebrated. Those saint's

days usually follow the same pattern each: On the night before the saint's

day, the celebrations start with the vespera at the place of the

festeiro. Festeiros are usually chosen according to their

status in the village hierarchy and their ability to finance food and

drink for hundreds of people. The participants of the vespera have

to stay awake the whole night drinking and dancing; they are not allowed

any sleep. At dawn the group, its members near collapse from excessive

drinking and lack of sleep, picks up the saint's new pole and flag, which

will stand in front of the church for a whole year, until the same saint's

festa comes round again. Pole and flag are painted in the saint's

appropriate colours, but with yearly differing patterns. The new pole

gets deposited on the ground in front of the church and some of the tired

folks go home for a nap. |

|

|

| |

|

At

noon everybody gathers at the festeiro's house for rice, beans and

meat. Not to mention the great amounts of cachaça and batida

that have to be supplied by the festeiro as well. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Fatima

as a very tired little angel |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

After

all bellies are filled, the procession starts, the statue of São

Sebastião gets carried around the village while the saint's

songs are sung and drums beaten. Back at the church, with little girls dressed

as angels looking on, the pole is raised and imbedded in the ground, where

it will stay for a year, until the next festival of São Sebastião.

A fellow holding two sticks dances in front of the saint, who, strangely,

gets cursed at and even beaten with those sticks. Onlookers get hit as well

if they venture too near. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

In the

evening there's forró, traditional dancing and merrymaking,

but attendance can be low, because many of those participants that were

up since vespera the day before have no strength left for yet another

night of partying. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

About

a week later, the festa of São Braz is celebrated. The festivities

are about the same as for São Sebastião, just the

songs and the colours of the pole and the flags differ. Fatima attended

São Braz in 2002 and took some pictures (click to enlarge)

: |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

On Páscoa

(Easter), the village youths visit the old folks, kneeling at their doors

to get a blessings and some cake. Fatima, who went along for the sweets,

told me that some mean old people used to scatter grains of corn and sand

at the thresholds to keep the youngsters off. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The biggest

event of the year is the festa of São João.

It's actually Midsummer Night, the Summer Solstice, only in Brazil it's

in the middle of Winter. |

|

|

| |

|

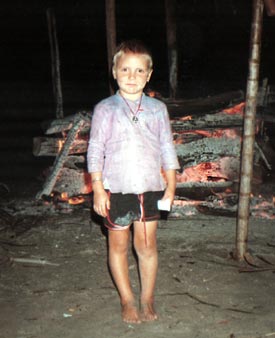

Starting

on June 22th the festivities last a whole week. The actual day of ,

the village's patron saint, is the 24th., the following days belonging each

to a different saint. It's a whole week of processions, dancing, revelry.

Drinking and eating is supplied at the houses of the respective festeiros.

Fogueiras (bonfires) are lit in front of homes, people gather around

the flames, telling stories and plying their instruments until the first

light of dawn. Housewives sell quentão, a delicious hot

drink made of ginger root, fruit juice and cachaça, that

warms both body and soul. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Rashid

at São João in his first year in Brazil |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

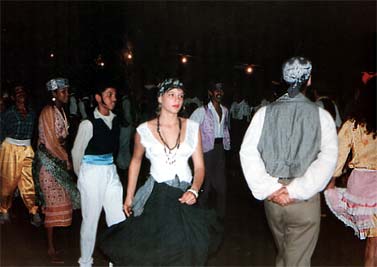

The

24th of June used to be long awaited by the village youths, who'd spent

a whole months with rehearsals for the dance of the quadrilha. Wearing

straw hats or scarves, the girls dressed in frilly dresses and the boys

in long trousers and shirts, the adolescents gather on the village square,

forming two queues, one for each gender, and the quadrilha starts.

|

|

|

| |

|

Dancing

to the commands of the leader located in the middle of the formation,

the lines of dancers form a circle, the circle dissolves into other patterns,

couples join hands, turn round, change partners. Each step and movement

follows the calls of the leader. On his call: "Olha chuva" (mind

the rain) hands are raised protectively above heads, hearing "Olha

pai da moça" (mind the girl's father) the couples stop touching,

"Olha cobra" (mind the snake) has the dancers jump over an imaginary

serpent. |

|

|

| |

|

Towards

the end of the dance, a fake priest enacts a fake "casamento"

(marriage) , in the course of which the bride gets abducted by a robber.

The quadrilha ends amidst great shouting and screaming. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Fatima

dancing the "quadrilha" of São João, around 1992 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Customarily,

for each day of a festa people, and children especially, needed

a new outfit. It took my kids a while to convince me of the importance of

buying new clothes despite there actually was no need for any. We had brought

many beautiful clothes from Asia, made of Indian silks and Chinese brocades,

and I'd have thought Fatima could wear those for special occasions. No way,

it had to be something new every time, it needn't be anything festive or

expensive, just new. That was the way kids in Trancoso got their clothes,

after the holiday the new outfits would be worn for school, play and work,

and until the net festa often were reduced to mere tatters. |

|

|

| |

|

My

friend and neighbor Zilda turned out to be a gifted tailor, happy to earn

a few coins, so I usually asked her to sew the clothes for my kids. She

made my dresses as well, from living in the East I was used to having my

clothes made according to my own taste and style. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Christmas,

the biggest holiday in most Christian countries, isn't very remarkable in

Trancoso. Though with ever more foreigners living there, this might be changing

as well. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Children's

birthdays were commemorated with much enthusiasm and huge, lovingly decorated

cakes. For my taste they were far too sweet, and often the main ingredients

were just flour and water, with some chocolate added. Anyhow, to the unspoiled

taste buds of the local kids those cakes sure tasted great. They had to

be cut into a great amount of small chunks, to allow all the youngsters

gathered around to make off happily with a tiny piece wrapped in a paper

napkin. Some kids suppressed the urge to devour their handfull of bliss,

and brought it home to share with their family. |

|

|

| |

|

Birthday presents

mostly were rather basic as well: A cake of soap, a tube of toothpaste,

or a pack of cookies. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

a typical birthday party |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

One thing

about those birthday parties I didn't like at all: Children often drank

alcohol. Nobody seemed to mind, it was the grownups themselves who gave

them cheap wine or home made batida to drink. As much as I told my own kids

to stay away from those beverages, Rashid more than once returned from a

friend's birthday with that telling gleam in his eyes. |

|

|

| |

|

What really

got me mad though was an incident on the occasion of Radhid's own birthday

at our place. I had bought some wine for the adults, and made it very clear

that none of it was to be given to any kids, they were have the the soft drinks.

Suddenly I saw my youngest, one year old Ahmed, teetering and, not being

able to keep standing, falling to the ground. I tried to help him stand

up again, in vain, he collapsed and started to cry. Something was fishy.

Ahmed seemed to be near to fainting and really ill. I showed him to a neighbor,

who took a good look and declared him as drunk!. I nearly went berserk. My neighbor

tried to calm me down, telling me that her own little boy, of the same age

as mine, had been drunk once as well. |

|

|

| |

|

Now that

didn't help me at all, I was fearing for the life of my baby. The only thing

we could do was massaging Ahmed's feet and putting him to sleep. Next day

he was OK again. It transpired later that a young neighbor woman had given

the little boy a whole cup of wine to drink. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

At night there often were parties in bars, on

the beach or at somebody's house. I never attended any of those, knowing

very well I wouldn't like it. Dancing to loud disco music had ceased to

interest me when I was sixteen and started to travel, my alcohol habit amounted

to hardly more then a cold beer once in a while after shopping in the dusty heat of Porto

Seguro, and I detest cocaine. |

|

|

| |

|

Even without any party, the bars bordering the village square

came alive in the evening, and all night long music was played at full power.

In summer season, bars and restaurants were crowded, tourists mixing with

locals to drink and dance. Off season, one might walk into one of those

tiny bars at three in the morning, drawn by the intensity of the blaring

sound emanating from its open door, to find nobody inside but the youthfull

owner sitting half asleep behind his counter. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

I seldom left our property if it wasn't to buy groceries for the restaurant or something else we needed. When Grande, our first mason, who'd stopped working

for us after a year to open a bakery, invited me to his birthday party I

accepted though. A party attended mainly by locals, without tourists or

rich dropouts from Brazil's south, was more to my liking. The natives back

then weren't into cocaine yet, though, alas, this was going to change soon. |

|

|

| |

|

So I got myself ready in the late afternoon and

left home to walk the few hundred meters to Grande's home. On crossing the

quadrado, a totally upset Fatima caught up with me, got hold of

my arm and cried: "No, Mama, you can't go." I don't know for sure

why she tried to stop me, I suspect she was shocked because it was so very

unusual for me to leave the house to go to a party. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Mother's

Day is duly celebrated in Trancoso as well. On one such Mother's day, we

mothers were called to the village school to watch our kids reciting poems

about, guess what, mothers. It was real sweet. |

|

|

| |

|

On my

first Mother's Day in Brazil, some women and youths were enacting "living

pictures" at the village church. An improvised curtain went up and

down, each time exposing a group dressed in costumes and arranged in a diferent

manner symbolizing something related with motherhood. Though why they chose

a young blonde with not yet any offspring of her own for the part of the

mother will forever remain a mystery to me. If anything was abundant in

Trancoso, it was real mothers of any type, even a few who had given birth

up to twenty (!) times. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Brazilians

love their children abundantly, and Children's Day is an important holiday, where the kids get spoiled and receive a few presents. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|