| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

After the house was ready and the restaurant

had opened, our life in Trancoso started to get a certain structure. |

|

|

| |

|

The first couple of months we had spent getting the feel of

the place, plying snooker and acquainting ourselves with the new language

and local customs. It was a somewhat boring period, there was nothing to

do actually except waiting for things to start moving. In this time we first

noticed how big the difference was between the orient and Brazil. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

my favorite window |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Daily life consisted of getting up around seven, woken by

the noise of my kitchen helpers, usually some young girls from the neighborhood,

entering and getting busy clearing away the debris of last night's cooking.

I do admit to being a rather messy cook, my excuse being that it's impossible

to be both creative and orderly at the same time. |

|

|

| |

|

I was glad to have a few girls around to do the chores I didn't care for.

This left me ample time to do what I like and I'm good at, which is anything

that challenges my creativity. |

|

|

| |

|

Most village housewives were meticulous housekeepers. It was most impressive

to see how they managed to polish a crude concrete floor until it was as

smooth and shiny as a mirror. On the other hand, I think they could have

used their time better for something more constructive, like maybe reading.

Actually reading wasn't at all popular, there was not a single newspaper

available in the village. One of my friends and neighbors used to "read"

once in a while, to her that meant going again and again over the same old

tattered religious pamphlet that was the only readable text she owned. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

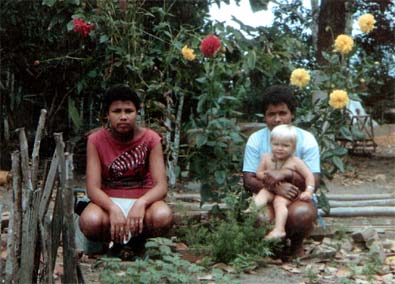

Zezé

and Sueli, two of my helpers in the kitchen and around the pousada |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Off season, by far

the bigger part of the year, the restaurant only opened in the evenings for

dinner, which gave me ample time to prepare the meals with much care and no hurry.

I liked it when friends came by to sit in the kitchen while I worked, we'd

talk, laugh and have a good time. During the short tourist season I also had toprepare breakfast for the guests. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Depending on the actual state of things, I had to confer with

our construction workers about the ongoing work. They'd learned to call

me before doing something rather than redoing it later because a certain

arch didn't have the curve it should or an ornament looked wrong. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Shopping was complicated and took up much time. Not only

did we need groceries and fresh vegetables for the restaurant; household

items and construction supplies also had to be bought or ordered. I regularly

made the bus ride to the edge of the bay and across by ferry to Porto

Seguro. Trancoso had only one small store with a very limited choice of

items and prizes much higher than in Porto, which boasted at least three

medium size supermarkets were located. On the wharf was a place to buy

fresh fish, and some old timers had set up a few rickety wooden tables

where they'd clean and cut the purchased fish according to the customer's

preferences. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

typical Porto Seguro residential

street |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Due to sky rocketing hyper-inflation it was advisable to compare

prizes in all three shops first, they changed on a daily basis. In all supermarkets

one could usually find some salesclerks occupied with changing prize labels

on all merchandise. I found a batch of tins of asparagus on the lowest shelf

in a store once, a vegetable hardly known or bought by locals. Accordingly

they didn't get their prize renewed for a couple of months and cost only

a fraction of their real value. |

|

|

| |

|

If I was lucky, my groceries were delivered to a street

corner near the ferry by one of the bicycle boys employed at the stores.

I still had to carry the heavy cartons and wooden boxes down to the boat

though and up again to the bus stop on the other side. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

waiting for the ferry |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

In bad weather there was always the danger of an old bridge,

consisting only of roughly hewn wooden beams, being defect or impassable,

or the muddy inclines leading down and up again where too slippery for vehicles.

So at times, the bus would stop up on the ridge on one side of the small

river, all the goods had to be carried down to and over the bridge and up

again, where a second vehicle waited to pick the passengers up. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The next bigger town after Porto was Eunapolis, farther inland

and some 80 km from Trancoso, an unappealing place with one of the highest

crime rates of the region. It was there we bought tools and different construction

materials like coloured glass for windows and ornaments, and also fabrics

for clothes. Getting to Eunapolis and back was a full day trip, undertaken

in our jeep when someone with driving skills was available, otherwise by

bus from Porto Seguro. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Ahmed and Quito sharing a seat on

the bus to Porto |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Prizes actually increased by 400% during my four years in

Brazil. Foreign exchange had to be converted to local currency only on the

day it was needed, to avoid any loss due to daily changing rates. We had

arrived with some traveler checks, and to cash them in at that time only was

possible in Salvador da Bahia, 600 km or a long night's bus ride from

where we lived. |

|

|

| |

|

I loved to visit the splendid previous capital of Brazil with

its majority of black people, tiny bars on steep narrow alleys

selling home made liqueurs from dusty bottles, and white-robed Bahianas

sitting on street corners deep-frying local dishes with African names

like carurú, vatapá and acarajé

in bubbling dendé, red palm oil. |

|

|

| |

|

Bahia, as Salvador, beautifully situated on the shores of

the huge Baía de todos os Santos, is generally called,

is a town of religion and mystery, of magic and cults. Catholicism

co-exists and often merges with candomblé, the black gods

and white saints exist side by side. Both are evoked to assist their suppliants

in handling and influencing their worldly affairs. Priest hold mass

in their lavishly decorated churches with gold-gleaming interiors

while on the next block maes dos santos in head scarves

and long robes whirl in trance and communicate with the old African gods. |

|

|

| |

|

The places we changed our traveler checks at were some mortician's

stores in the historical town of Salvador, with coffins displayed both in

the shop windows and inside. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

After a year or so in Trancoso, Fatima's Portuguese was well

enough for her to enroll at the local school. The drab concrete school building

consisted of only two rooms in the beginning, and classes didn't go further

than fourth grade. A few years back, the sole tuition available had been

lessons given by an elderly lady, a retired schoolteacher I think she was,

at her home. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

With time, a bigger school was built, and classes in higher

grades were added. Hundreds of Brazilian families from the interior moved

to Trancoso, where the resident foreigners provided some hope of finding

work in construction, so the facilities of the new school weren't sufficient

either, and classes had to be held in shifts until late at night. |

|

|

| |

|

To qualify as a teacher in Trancoso, not much more then a

basic knowledge of the alphabet was necessary. Some teachers were volunteers

from the southern states who happened to get stuck in the village. One of

my kitchen helpers aspired to the noble calling as well, despite not being

able to write a grammatically halfway correct daily menu on the blackboard

out front. |

|

|

| |

|

Fatima would get up by herself every morning and groom herself

nicely for school. In maybe her third year, her grades in Portuguese were

getting better than those of her native friends, who weren't pleased at

all. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

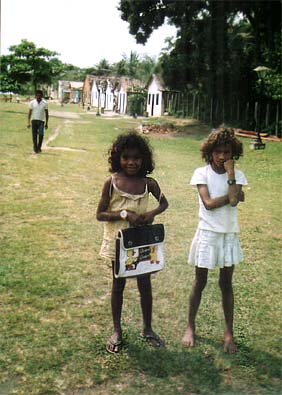

two of Fatima's schoolmates |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Rashid didn't learn as easily. When we had left Nepal, he

didn't speak much German yet, he had communicated with Fatima and their

playmates in basic Nepali. Since he hardly ever was home in Trancoso, his

German didn't improve. He instead picked up the local dialect, far removed

from proper Portuguese, where, as an example, flor was pronounced

fro. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

One unforgettable afternoon I was busy in the kitchen when

Rashid appeared and started to talk to me very rapidly. My own Portuguese

by then was about passable, but I had acquired it not only from the locals,

but as well from talking with better educated friends from other states,

and from reading comics. So on that day, when my son stood in front of me,

excitedly babbling in heavily accented local lingo, I couldn't understand

a word he said. I asked him to slow down and speak more clearly, to no avail.

I urged him to try in German, but it was hopeless. The more frustrated he

got, the less I understood. His face colour changed first to red and soon

to purple, his big eyes were brimming with tears and he looked as lost as

I felt myself on realizing I couldn't communicate with my own child. Finally

I had to call for one of my kitchen girls to find out what Rashid was trying

to tell me. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Little Ahmed didn't pick up any German from me and his father

either, and soon I only talked Portuguese with both the boys. Fatima still

knew some German from a year spent in Stuttgart when she was four. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Two years after Fatima entered school, it was Rashid's turn,

though he didn't show the same enthusiasm as his sister. Rashid and his

friends, as young as they were, proved to be indomitable for their first

volunteer teacher, a nice, soft-spoken girl from Minas Gerais. After three

weeks she fled Trancoso, having lost both her nerves and her voice. Next

came a rather impressive young woman, a heavyset Obelix look-alike, whom

I expected to have more standing power. She capitulated after one month. |

|

|

| |

|

Only a real tough lady from Rio and village nymphomaniac by

reputation managed to get the boys sorted out in the end. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Rashid (center) at school parade |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

In the first year of school, daily lessons amounted to one

and a half hours only. Not much actually, but seemingly still too much for

Rashid and his mates. I learned from the teacher that often my son didn't

turn up at school at all, or if he did, he came late and left at intermission. |

|

|

| |

|

On being questioned about the reasons for not attending

classes on a certain day, Rashid gave me one of his innocent looks and

explained they'd been busy helping a mate to transport some wood back

to the village with his father's ox. In the boys' opinion, and in only

too many adults' as well, any such activities naturally were of higher

priority than attending classes. |

|

|

| |

|

It got worse after I left Brazil. Rashid had to repeat third

grade thrice due to falling short of the required number of hours of yearly

school attendance. |

|

|

| |

|

Only many years later I learned from my son how naughty he

and his friends had actually been. He told me stories like the one about

how his best mate used to ask permission to visit the loo during lessons.

This being granted, he'd escape, or, on the refusal of the teacher, who

well knew his intentions, he'd piss right on the classroom floor. Another

pastime of those little malandros was to explode self made bombs outside

the classroom windows. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Woe to the teacher who dared cuss out an unruly pupil. Fathers

would appear at the school building foaming at the mouth and brandishing

machetes, defending their blameless little lambs against the injustices

of the scholastic world. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

One of Rashid's mates once asked his father if

he couldn't take off a year from school. The father, of a generation that

hadn't gone to school at all and still was not completely convinced of the

importance of such customs, acquiesced easily. In hindsight, it maybe wasn't

so wrong a decision, because the lad later died at the age of nine. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

In the evenings, the village green served as a soccer field

where the younger men, after ending their workday, gathered for a game,

watched by their female contemporaries. On Sundays some more important matches

were played, often against a neighboring village. Half the place, grandmothers

and matrons included, would watch the Sunday games, relaxing in front of

their own houses or those of relatives bordering the quadrado. |

|

|

| |

|

Among the girls, futbol was very popular

as well, and Fatima, the only one of my kids who loved to play soccer, wished

to join a girls team. I tried to talk her out of it, not liking the idea.

Most of the players were of rather stocky, square build, with the grace

and power of steamrollers, and I feared the worst for my girl's more delicate

bones. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Something else the kids liked was to watch TV. We never had

owned a TV set in Nepal, and neither did I want one in Brazil. When I needed

Fatima, I often found her at our neighbor's, sitting on the parlor floor

among a group of friends, their eyes glued on the latest "telenovela". |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

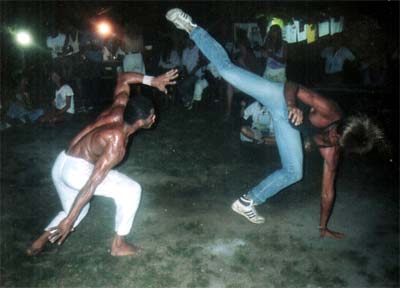

As the village grew, new types of recreational

activities were introduced. Capoeira, a kind of weaponless defense

developed by negro slaves, who were prohibited to carry arms, evolved into

a fashionable sport all over Brazil, and was, contrary to tradition, embraced

by women as well. Meanwhile, Capoeira has spread to all corners

of the world, and there is hardly town in Europe or Northern America without

at least one school of it, led by some mestre of minor or major

fame. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Capoeira in Trancoso |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Two opponents "fight" against each

other, though the fighting is rather a very elegant and acrobatic type of

dancing, the two players whirling and jumping to the sound of the accompanying

music of drums and berimbau and the traditional songs sung by the

circle of their friends and fellow capoeiristas.. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

drums and berimbau accompany

the capoeiristas |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Trancoso has no real tradition of Capoeira,

unlike the state capital, Salvador da Bahia. But among the Brazilian

drifters and dropouts hanging out in the village, there were always a few

who knew how to play, and would gather to show their art in the evenings. |

|

|

| |

|

For more info on Capoeira click below. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Brazil

had (and I assume still has) a very strict policy against the use of marijuana.

I've heard accounts of electroshock therapy being applied to offenders still as late as the

eighties. Luckily, due to the absence of a police station in our village,

grass could be smoked in relative peace. Not too openly, but inside buildings

or in the quintals, the backyards, joints could be passed around

without causing problems. We had our pond in the garden to sit around, or

the roof of the small pousada building. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

A funny and memorable incident comes to my mind,

starting with a respected local man and a butcher by profession paying us

a visit one afternoon, hinting he had come as a friend to give some important

advice concerning a certain matter. He didn't outright declare his mission,

and when he did after settling down with a cold beer, we were all the more

perplexed. "It's about the pé", he confided in

hushed tone. The pé??? |

|

|

| |

|

Now pé means two things, first

it's the Portuguese word for "foot", and second it's used in relation

to plants, mainly trees or bushes, as in "pé de laranja"

for example, meaning an orange tree. |

|

|

| |

|

We still had no clue, and our visitor

further mystified us by producing a small card from his wallet, identifying

him as a police agent, but reassuring us at the same time that he had come

as a friend. Someone had informed him that we had a "pé

de maconha", a cannabis plant, in our garden! |

|

|

| |

|

A quick check proved him right, one solitary

grass plant really stood near the pond. Only we had never noticed it, it

must have grown from a dropped seed. As the corpus delicti stood

in full view of a somewhat unpleasant neighbor, it was not difficult to

deduct who had ratted on us. |

|

|

| |

|

Mr. Secret Agent told us to uproot and destroy

the offender, which we immediately did, having no use for a male plant anyway. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

One day around Christmas in our second year in

Trancoso, a guy who'd just come up from the south told us about a boat at

sea who, for unknown reasons, had thrown its cargo consisting of first grade

marijuana, sealed

in tins, overboard somewhere near Rio. Well, Brazil is full of stories,

and not half of them are true. That's what we thought. |

|

|

| |

|

About two weeks later though, another friend

returned to Trancoso not only with the same story, but with some samples

of the grass. It was terrific, after smoking only one jillum I

felt like walking on air on the way back to my kitchen. One thing

was for sure: That wasn't local stuff. As to where the boat's cargo had come

from, nobody knew, but a lot of guessing went on. |

|

|

| |

|

Now this friend told us how he and some mates

had been relaxing on a beach in some southern town, when they had noticed

a few big tin cans lying around. Curious, they picked one up and opened

it, and couldn't believe their eyes: It was filled to the brim with grass.

No question, they gathered all the tins they could find. What a welcome

Christmas surprise for hundreds of potheads all along a great stretch of

the sea shore, and a great story to one day tell their grandchildren, who

of course will not believe one word of it! |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Unfortunately,

the use of cocaine is very popular in Brazil too. I've witnessed some rich

dude ordering an empty plate to snort his "dessert" right at his

restaurant table. As much as I'm convinced that cannabis is a benevolent

mind opener, as much I'm against cocaine as a "recreational" drug. |

|

|

| |

|

It's conceivable that some natives in the Andes

chew the leaves of the coca plant without too many adverse effects, after

all it's a traditional part of their culture. I've never been there and

therefore I don't know. What I do know though is that cocaine powder is

one of the most dangerous drugs around. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The repercussions of coke abuse on the mind are

bad enough: Dumb people feel so great and enlightened that as soon as the

illusion ceases, they have to take another snort. I've spent endless hours

watching folks high on coke when my ex was partying with his friends. Everyone

thinks he's talking pure philosophy, when actually it's complete bs that

doesn't make any sense. Two people discussing something at times don't

even notice they're talking about completely different topics. Coke is a

drug that bloats the ego, and is a great danger mainly to people with low

self esteem, who under its influence perceive themselves as brilliant and

in complete control. |

|

|

| |

|

This can go on for a time, sometimes even for

a few years. But the next stage usually is one of hallucinations and terrible

paranoia, up to the point where addicts have delusions like believing that

everybody they know, friends and family included, takes part in a huge conspiracy

to kill them. |

|

|

| |

|

Cocaine also gravely damages bodily tissue, I've

seen photos of brain scans where big lesions were visible, and met people

with actual holes in the bones up their noses. |

|

|

| |

|

More upsetting for me though was the fate of

babies and children of coke abusing parents. The luckier ones who didn't

have grave birth defects still were so much slower in their development

than their contemporaries. One little girl I knew was born with a disease

that spelled total blindness from about the age of 14 years onwards. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

A few years after I had left Brazil, I heard about locals

getting involved with the powder as well. Now the rich southerners and most

of the foreigners at least can afford their habit. Natives can't, and coke

being the cause not only of bodily ruin but moral collapse as well for many

a native lad. The first murder of a tourist in Trancoso got committed by

an addicted young local. And a nice woman I knew left husband and three small children

to join a gang of bandits after she got hooked. |

|

|

| |

|

But enough of this exasperating topic. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Through my kids, neighbors and friends I learned about the

local superstitions, fears and legends, which include anything from the

headless mule, mula sem cabeça and the chupa cabra

(literally: goat sucker, a feared beast that reportedly sucks animals

empty of their blood), the latter being known all the way up to up to Mexico,

to beliefs like the one stating that in Brazil men and women exist at a

ratio of 1 : 7. Meaning if for every man their are seven women, staying

with only one deprives six less fortunates of the pleasure of male company.

A good excuse to leave a women when she gets pregnant and move on to the

next one. |

|

|

| |

|

Accounts of supernatural occurrences, of the appearance of ghosts and

of haunted places abound in rural Brazil. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

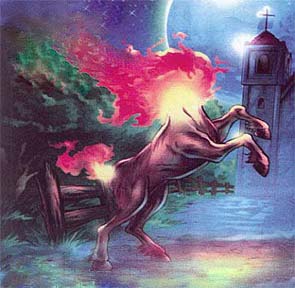

Mula sem Cabeça (picture: web) |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The Mula sem Cabeça is said to be able

to inflict severe wounds with its sharpened hoofs on the hapless victim

who happens to cross its path. Legend has it that women who committed

some wrong, especially those having a love affair with a catholic priest,

turn into such frightening creatures with roaring flames in place of a

head on Thursday nights. |

|

|

| |

|

Though in Trancoso, the Mula sem Cabeça only appears in

the Semana Santa, at Easter Holiday, after midnight. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Saci pererê (picture: web) |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

A figure well known all over Brazil is Saci pererê,

a one-legged pipe smoking Negro boy with a red cap. Fatima told me that

when she and her friends went to collect wild growing fruit, they were

very careful about not following any bird. It was well known that the

Saci could change into that form and would use it to enthrall the

kids and abduct them. Saci also is known as a mischievous sprite who loves

to play pranks. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

There is a kind of a grotto with water dripping from the stones on the

way to Porto , where many people have seen a mysterious old lady appear.

Kids wouldn't go near that place out of fear. |

|

|

| |

|

. |

|

|

| |

|

Considering that in its past Trancoso had witnessed slave trade in all

its cruelty, I'd be the last person to deny the possibility of a few unhappy

and wronged souls still being attached to the place. Whispered insinuations

hinting of a massacre committed on native Indians only a few dozen years

ago, with some of the participants still living in Trancoso, make for even

more violent deaths having taken place in the village's vicinity. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Myself, I have never encountered any disgruntled

spirits though, and I suspect that a great part of such sightings were either

drug or alcohol induced, or in the way rather of what once happened to Fatima

and her friend. One evening after nightfall those two young girls came running

home in panic; trembling with fear they told of a terrible beast with eyes

like glowing embers they had encountered just outside the quadrado.

Curious, I asked them to show me the place where they had seen the

monster. Arriving there, I soon made out the culprit responsible of reducing

two bold girls into shivering scaredy-cats: A discarded, squashed soft-drink

can that lay in the darkness of a small wayside ditch reflected the light

of a nearby street lamp, so producing the two shining spots that the girls'

vivid imagination turned into the luminescent eyes of some ogre lying in

wait. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Another widespread fear was that of the onça,

some kind of a jaguar. At times it was so bad that some people were afraid

to walk around the village after nightfall. One of the girls working for

me was scared enough to refuse to stay alone in the kitchen behind the house

at night. I don't know when the last jaguar was seen around Trancoso, but

during my four years stay nobody actually ever saw one. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

One winter, strange stories of discarded children's

bodies found in back alleys of neighboring towns, eyes or organs missing

and wads of money stuffed into their clenched fists made the rounds. Every

stranger passing through the village was eyed with suspicion, and woe to

the one who stroke up a harmless conversation with a local kid. Nervous

mothers kept a much sharper than usual control on the whereabouts of their

offspring, and neighbors watched out for each other. I never was able to

make out if any such incidents of abduction really had actually occurred,

or if all those stories were just urban legends. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|