|

if your browser doesn't support the menu, please use the links at the

bottom of the pages

|

||

|

||

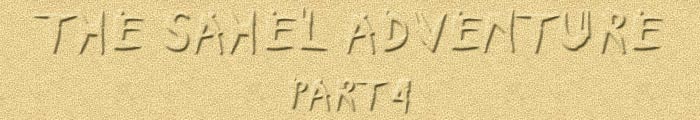

our route from Ingal to Niamey |

||

| Every day at noon, the camels invariably needed to rest. They were accustomed to a midday pause and outright refused to continue when the sun was at its zenith. Accordingly, twice every day we had to occupy ourselves with the time consuming procedure of properly fixing up our bags and bundles. As mentioned earlier, a third camel solely for the luggage would have been convenient indeed; unfortunately, we didn't have the money for one. | ||

|

||

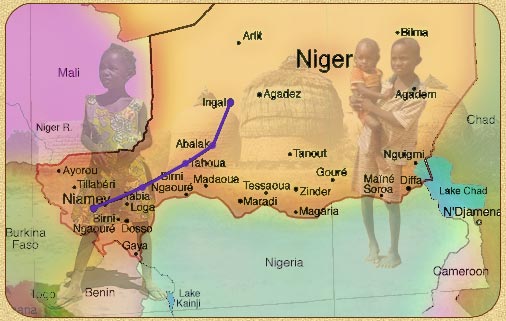

| The young man insisted we should accompany him. He assured us that nobody wanted anything from us, no presents were expected, the chief solely wanted to meet us and to offer us his and his tribe's hospitality, including food and a place to sleep, and fodder plus water for the camels. Considering it futile to further refuse, even knowing by now very well that people in this part of Africa weren't interested to meet strangers without the hope of some material gain, we gave in and followed the lad to his camp. | ||

| On our arrival there, we were duly greeted by the chief, a tall slender man maybe in his thirties. Again we explained that we had nothing to offer, and actually would be happy to continue on our way. To no avail; the chief too insisted that no presents were expected, and showed us the place we were to spend the night. | ||

| It turned out to be a very simple, tiny hut, four straw walls and a straw roof set upon sand, otherwise empty and barren. We later found out that this shack usually served to house passing tax collector and other government functionaries. | ||

|

||

tuareg camp |

||

| Having unburdened our animals, we let the slave in charge of the tribe's camels lead them away. I actually mean slave, slavery wasn't abandoned yet in the Sahel region, and up to this day it still isn't. I remember once encountering a young lad on the road, and asking him, out of curiosity, about his ethnicity. Expecting him to tell us he was a Haussa or a Songhai, we were dumbfounded on when he answered us that he was a "captive", a slave! | ||

| Additionally, from talks with Tuareg people we learned that the dark-skinned members of the tribes originally used to be the slaves of the lighter-skinned ones; they probably still are treated accordingly. | ||

| (I saw a TV documentary a while ago about an organization in Niger that helps slaves to escape. Most of the shown cases were women who somehow found the courage to run away from their owners, though that usually meant leaving their children behind. With the help of said organization the children were freed and returned to their mothers. First thing shown was the story of a young slave woman from Tchin Tabbaraden, the precinct In Waggeur, where we spent those two days with the Tuareg tribe, belongs to.) | ||

|

||

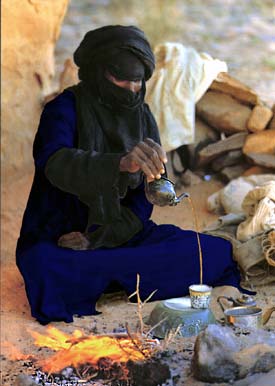

preparing tea; Photo: postcard |

||

|

||

| On our own, we used less tea leaves and consequently enjoyed a far milder brew. | ||

|

||

| What happened next was yet to become a common part of our African experience: People started to tell us about their ills and diseases and to ask for medicines. We patiently explained over and over that we had no medical knowledge at all, a fact that seemingly neither impressed nor concerned anybody. The belief in the magic of the white man's power was unshakeable. Not until we handed out some pills we happened to have in our luggage, left over from X's hand injuries and some occurrence of diarrhea, were they content and left us to sleep. | ||

| The entire day passed like the evening before: We sat rather bored in our bare hut, sharing our tea, tobacco and whatever pills we thought fitting with the frequent visitors from the tribe. In the afternoon the chief himself passed by, promising to come back next morning to give us directions for our onward journey. | ||

| Again, no food was offered to us on our second day. Not that we had a mind to deplete the tribe's food stocks; I only mention the issue because the young man who had extended the invitation to us back on the track had promised we'd of course be the chief's guests in that respect. And from experience we knew that those chiefs' tents were usually filled to the roof with the food rations that were actually meant for the tribe's needy. | ||

|

||

| In the middle of the ensuing argument with the camel boy, the chief made his appearance. Somewhat sheepishly we held out to him our box with the dates. Having understood that we refused to pay more than a few coins to the slave boy, he looked at his gift with disdain, grabbed it and, without a word of good bye, turned on his heel and made off. | ||

Even without the promised directions, we were relieved

to get away from the camp and soon were back on our track again. |

||

|

||

|

||

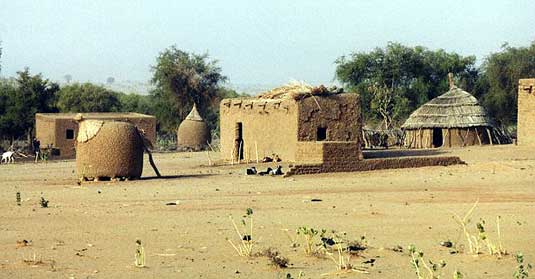

typical village with granaries along the road;

photo:Galen R. Frysinger |

||

| Not only the camels had a hard time though. I often remarked to my spouse that this trip was harder than working in Switzerland. We were occupied from dawn to late at night. It would have been easier with a few more people to share the chores. As it was, we enjoyed the trip but fell asleep totally exhausted every night. | ||

| The climate was fantastic, every day sunshine, a blue sky, and very dry air. As we were traveling during the hottest months of the year, we hardly ever needed to pee. I've read that in 1974 temperatures in Niger came up to 60°C in the shade. Dry as it was, we didn't sweat, at least not noticeably. At night I guess it must still have been around 45°C, otherwise I couldn't have slept without a cover. (I used to travel with an old 4 kg eiderdown in India, and while everybody else employed only the thinnest of fabrics as a protection against insects, I slept happily with my heavy cover up to my nose at 36°C or so.) | ||

|

||

Sahel rock formation; photo: web |

||

Every morning we rose at dawn. To prepare tea, pack

our bags and bundles and tie them to the saddles usually took about

an hour; at least that's my guess, of course we didn't have a watch.

Then we'd ride till near noon, when we'd start to look out for a resting

place that afforded a minimum of shade, like some leave less trees or

a big rock. After unloading, we went in search of twigs to feed our

cooking fire while the hobbled animals roamed for some mouthfuls of

dry grass or pursed their lips to eat the tender leaves growing between

the long spines of the acacia trees. |

||

|

||

acacia leaves: a preferred treat;

photo:web |

||

After building the fire, cooking and eating our rice with the inevitable sauce made of dried onions, garlic and dried tomatoes, it was time for another tea. Once the pleasant part of the rest being over, we had to do chores like cleaning pot and plates with the barest minimum of water, repairing our leather sandals or saddle belts, trying to figure out our position and the next water source on the map and while keeping an eye on the grazing animals. |

||

|

||

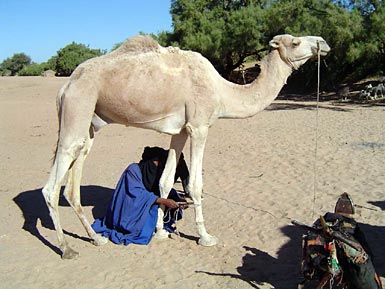

Tuareg hobbling his mount; photo: web |

||

| Having caught the animals and secured our belongings, we usually rode until the sun touched the horizon, when once more it was time to look out for a spot to rest and sleep. At night we had to tether the animals, otherwise we wouldn't have found them again next morning; even hobbled they could easily have covered a great distance while we were asleep. | ||

| The nights were magnificent. Using our saddle blankets fort pillows, we lay beneath a canopy of velvety bluish-black sky glimmering with thousands upon thousands of stars glittering like diamonds scattered by some mythological goddess. Frequent shooting stars streaking the sky enhanced the spectacle, I couldn't get enough watching a sight as beautiful as I had never before seen . | ||

|

||

| Spider were not the only desert life we came across. One night we went to sleep beneath some shrub like small trees. We were just starting to doze off when our skin started to itch all over. Taking a close look we found dozens of ticks which had dropped from the branches of the bushes onto our bodies. As fast as possible we gathered our belongings, moved somewhere else and started to remove the bloodsuckers from our skin. | ||

Another evening, when we just had unloaded the animals, a small scorpion scurried about our chosen campground. Too tired to upload our baggage once more, we killed the poor critter, feeling rather guilty afterwards for having thus extinguished an innocent life. |

||

|

||

|

||

a victim of drought and disease; photo:web |

||

| Never before nor afterwards have I ever smelled anything so vile. During the great drought of that time, 80 - 100% of all livestock in Niger's Sahel zone perished. In addition to the lack of water, some epidemic also took its toll on the animals; our guess was foot and mouth disease, but we didn't know for sure. | ||

| I vividly remember an encounter we had one morning with a Peulh herdsman coming from the opposite direction, guiding a few meager heads of cattle. The man eagerly asked if the region we came from was free of the disease; we had to crush his hope by telling him it was rampant in all the places we had passed through. We felt very sorry for the unfortunate fellow, but there was nothing we could do for him. | ||

|

||

Peulh herdsman; photo:web |

||

| For thousands of nomads in the Sahel, their animals are their only possessions. Loosing those animals often means a life without a future, a life in abject poverty for them and their families. | ||

|

||

|

||

Sahel sandstorm; photo: web |

||

| With the world all around us reduced to nothing but sand and wind, what could we do but wrap some rags around our faces, huddle down and wait. As it was already late in the day and maybe two hours had passed without any change of weather conditions, we decided to make the best of the opportunity and turn in early. The camels would have to go without dinner; with visibility near zero there was no question of letting them roam in search of fodder. For fear of loosing our mounts we tied them to the saddles we were leaning on. The animals, not accustomed to sandstorms themselves, for once made no fuss, obediently sat down and rested alongside us. | ||

| Waking up early next morning beneath a clear blue sky, to our great astonishment we found that we had made camp only a few meters away from the tracks where every once in a while a truck passed. We were lucky we hadn't slept right on the trail, or we might have met an untimely end as road kill right in the middle of the Sahel desert! | ||

|

||

goatskins filled with water; photo: web |

||

| In the desert heat, the water in the goatskins tends to pretty much evaporate over the course of two or three days; so often what we had left was a thick blackish soup that we drank by way of covering our mouths with the ends of our scarves and slurping the liquid through that filter. As to the quality of that brew, no comment. Suffice to say, we once thoroughly shocked some village kids who watched us emptying the last dregs from our goatskins. On seeing the black stuff trickle from our skins, those urchins in a godforsaken tiny village at the end of the world stared with round eyed disbelief. One boy was bold enough to asked us in French if we really had been drinking that mess, while his friends shyly giggled. | ||

| The most remarkable source of drinking water I remember though was a muddy puddle occupied by half a dozen goats. The water was contaminated with hundreds of pellets of goat shit. We actually had no choice but to drink from that somewhat unwholesome liquid after filtering it through the usual piece of fabric, and to fill our water skins with it. It was the only water available. | ||

| Being rather resistant from several years of traveling, we didn't give much thought to such trifles as the purity of drinking water; we drank whatever the natives drank, and sometimes worse, without ever suffering from any adverse effects. During the entire trip we were in excellent health, possibly in part due to the sterile desert environment, where germs don't have much chance of survival. Small injuries to the skin healed immediately, without getting in the least inflamed or infected. Same with my mate's cut fingers, they had healed easily and quickly. | ||

| Whenever our water got scarce we had to ration it carefully to just a few sips every couple of hours. Under such circumstances, we usually felt much thirstier than we ever were with a still ample supply. The preoccupation with the coveted liquid even shaped my nightly dreams, made me continue longing for it in my deepest sleep and was the foremost thing on my mind upon waking | ||

|

||

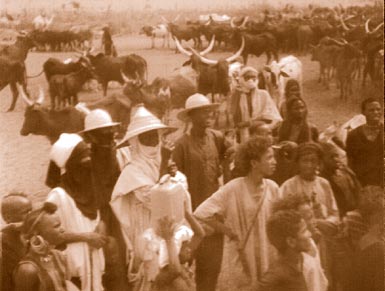

Tuareg and Peulh herders at watering place |

||

| It wasn't to be the only time we happened upon such a miraculous well, some time later we once more encountered one. We'd have loved to ask a thousand questions about those wells, like why there were not many more of them when thousands of people had to flee and animals perished due to the lack of water. As it was, at neither well did we find somebody who knew enough French to answer and explain. | ||

|

||

stopping at one of those miraculous wells |

||

| The above photo shows how the camel's head had to be bent back prior to mounting. To the onlookers, the sight of a woman riding and handling a camel was strange enough to arouse their curiosity. | ||

|

||

village mosque; photo:Galen R. Frysinger |

||

Only once did we meet a group of men who obviously adhered to the teachings of the Qu'ran. Those hospitable people for a change didn't ask a thing of us, but offered us a delicious bowl of fresh camel's milk. A lively conversation ensued in a mixture of French, local expressions we had picked up and Arabic, of which the leader of the group, a bearded elder, knew from his Qu'ranic studies. Of course we were far from fluent in Arabic ourselves, but having previously spent maybe half a year or longer in Syria and Lebanon, spending our day with local friends who didn't know a word of any foreign language, we could at least communicate. |

||

| Such encounters with kind strangers not interested in whatever presents we might, by some magic known only to whites, produce from our bags, but just content on meeting us and exchanging a few words, were rare indeed. During our stay in West Africa, they were so few I still remember about every single one a good thirty years later. | ||

|

||

back to main index |

||