|

if your browser doesn't support the menu, please use the links at the

bottom of the pages

|

||

|

||

selling calabashs at Tahoua; photo:web |

||

First thing we noticed when moving to the place were

the grass plants growing in the tiny garden, a pleasant surprise. We

spent two days cooking, eating and smoking; only leaving the house to

look after our animals. It was great to rest from the exertions of the

trip, |

||

| On arriving at the place of Joe's friend, we had tied the camels to a post near the unpaved dirt alley on which the house was built. Not a very clever idea, because soon some kid came calling us out front, where one of the animals was missing. We found the escapee somewhere further down the road, its nose ringless and its nostril torn. Sure enough, the cord with the ring was still attached to the post. The kid who'd called us had witnessed what had happened: A passing truck had made the animal jump with fright, forcefully enough to tear the ring from its nostril. | ||

| Using a piece of strong black thread I stitched the torn nostril together. | ||

| Next we had to find a safer parking lot for the camels, which wasn't very difficult. Somebody living nearby offered some free space in his backyard in exchange of a few coins. | ||

| Two days later it was evident that the torn nostril was not going to grow together again, my bumbling attempt at the veterinary trade had failed miserably. There was nothing left but to call somebody to pierce the poor creature's other nostril and attach the ring there. | ||

|

|

||

| Peuhl shoppers

at Tahoua market; photo:web |

||

| I was to remember this incident later on in the countries we passed through after leaving Niger, whenever some Peace Corps friends were to tell us that it was only too common for many West African women to welcome the opportunity of earning a few coins on the side. Back then in Tahoua I was just astonished; the woman obviously wasn't a regular prostitute, but a vendor of vegetables. Well, I was still new to African customs. | ||

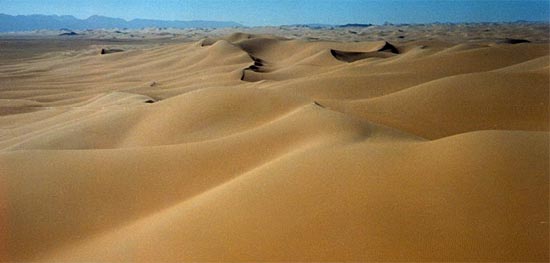

| Habitations still were scarce, and often for several days the only moving thing we met were whirling dust devils of about one meter in height. Those, according to local belief, are jinn, and it is said that a knife thrown at them will draw blood. | ||

|

||

| One such afternoon we were riding alongside, him once again cursing and shouting at me for no discernable reason, he attempted to hit me with the camel whip. His sudden movement scared my camel, which broke into a gallop. The other mount, carrying the enraged X madly brandishing his whip, followed suit, the water skins hitting the camels' sides and my screaming further increased the beasts' panic.............it must have been quite a sight. As the camels ran at a mad pace, bags started to tumble and fall, and after both X and the animals had calmed down again, we had to trudge back to collect what we had lost. More leather straps than usual needed to be mended that evening. | ||

We were easily convinced, and the next morning we left in direction of the first village on the schoolteacher's scrap of paper. Without fail we found our destination and spent the night in its periphery. At dawn we went to the only well in sight, a shallow hole in the ground where a woman was busy scooping up the small amount of murky liquid that had gathered at its bottom. On being asked where we could find sufficient water to fill our skins, she only shook her head. A passerby informed us about the local water situation: The coveted liquid was very scarce, and to fill our bags would take a great amount of time. It would be much better for us to continue until the next hamlet, only a few hours away, where we'd find plenty of water. |

||

|

||

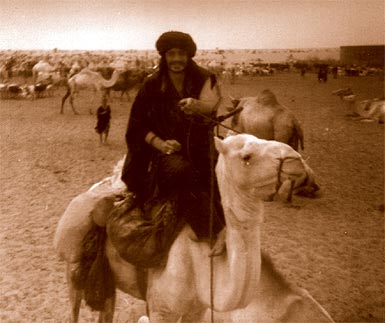

X on the white camel |

||

| After another hour X, who rode ahead, suddenly called out for me to come and look what he'd found: In the middle of nowhere lay the broken and crumbled remnants of a straight road leading to only God knows where. Clearly the road hadn't been used for many decades, it was all overgrown and had great gaps. | ||

Happy to have found something at all, we decided to

ride near that path of rubble and find out where it led to. The sun

rose higher and higher, and we stopped to drink a mug of water. What

trickled out of our skins though was only some thick black and brackish

soup. Filtered through a piece of turban cloth, at least a few mouthful

of that foul liquid could be collected in the mug and shared among ourselves. |

||

| What should we do? Could we allow ourselves our habitual rest? Being evidently lost, as we by now had realized to be, and without any water at all, we decided no; we couldn't afford to loose time. | ||

| Whom we didn't consult though were the camels. As well used to having their rest at noon, those two stubborn devils outright refused to go on; the meaner, white one carrying his mutiny to the extent of collapsing into a sitting position right on the spot where it stood. | ||

| For a while my own camel was still halfway manageable though it would try to sit down as well at least every few steps.The white one just wouldn't budge anymore, and thus encouraged it didn't take long for its companion to follow suit. | ||

| Well, it worked, by keeping the rein tight enough to make it impossible for the camel to turn its head backwards another time I saved myself from getting bitten some more. | ||

| No amount of coaxing, begging, or cursing nor the use of the leather whip could convince the white camel to get up again. Under the merciless glare of the noon sun, we started to feel pretty desperate. Lost in the wilderness without a drop of water, we wouldn't last very long. | ||

|

||

drawing some curious looks |

||

(visible in front is our sturdy mail saddle) |

||

| By now even X. had reached the conclusion that it would be wiser to turn back and to try to find the village we'd left at dawn that morning. Easier said than done. Villages could be hidden behind any hill or dune that made up a big part of the landscape, and we could easily have ridden past one without noticing. Employing the compass helped to show us the approximate direction we had to take, but nothing more. | ||

| I felt strange sitting on the white camel, which was meaner but smaller. I had thoroughly gotten used to my tan's height and way of moving, and didn't feel comfortable on the other one, which was still renitent and foaming at the mouth. Actually it was so unwilling that one of its teeth was broken off by the rope pulling it forward, changing the colour of the foam issuing from its mouth into a vivid red. | ||

|

||

Sahel dunes, Niger; photo:web |

||

| Slowly the afternoon had passed and the sun was ready to touch the horizon. Dusk being very short that near to the equator, we normally would have been looking for a place to spend the night. But this time there was no question of making camp, we had to move on as fast as our tired mounts were able to. The white one had meanwhile somewhat accepted its being towed and was less obstinate, probably both animals could sense our growing desperation. Was this to be our end, lost and dead of thirst in the wilderness of the Sahel desert? | ||

The last two hundred meters were covered with renewed

vigor, and with feelings of elation and gratitude we approached the

settlement. |

||

|

||

village kids in front of their hovels |

||

| Courteously we were led to an empty hut, and while some youngster was tending to our animals' needs, we were first treated to a cup of water. As nobody in the village spoke anything but Hausa, communication was rather limited. The three friendly chieftains now called for the usual millet drink, made of crushed millet, sour milk, water and pepper (actually we were more used to the sugary variety), to be brought for us. Not just one calabash full of it though, but several. Careful not to offend anyone, we decided to drink some of each vessel. | ||

| Later on the chiefs placed a big platter containing an entire cooked chicken and a calabash with milk before us. | ||

| Up to this moment we had been strict vegetarians and hadn't touched any meat, fish or poultry for about 6 years. But how to explain that to our hosts, who, even if a common language would have been found, hardly would have understood the concept of vegetarianism? | ||

| So we ate of the chicken; it tasted excellent. Exhausted from the day's trials and with our stomachs filled, we wanted nothing more but to sleep. | ||

|

||

village mosque |

||

| When the sun was in its zenith we got another four calabashes of the soupy millet drink, which definitely was too much; we got stomach problems accompanied by plenty of foul gases. Relieving the latter posed a problem; we hardly ever were alone. Since breakfast, our hut was continuously filled with curious villagers, who from time to time, amidst great laughter and shouting, got chased out by some elder wielding a wooden stick. | ||

| Later on we were called out of our shack and offered three live chicken. With some difficulty we managed to refuse that generous gift, not intending to rob those very poor people of valuable food stock. One of the offered birds probably was the main attraction of our dinner later on, served together with maize, milk and another three bowls of the by then dreaded millet drink. | ||

|

||

pounding millet; photo: web |

||

| Escorted to the end of the village and with directions for our way back to Tebaram, we rode forth with enough water in our skins to last us through the day. It took us only a good hour though to get back from where we had left two days ago; at least we had ridden in approximately the right direction when we had tried to make our way back. | ||

|

||

| Another teacher who was present invited us for a fine meal consisting of a dish similar to polenta, made of good sweet golden colored maize served with a tasty sauce. Only rarely that we seen such a good variety of maize in Africa; often we ate maize of a very inferior quality, possessing a greenish colour and a sour, unpleasant taste. | ||

| Later on in Benin we were to buy a horrid greenish type maize, sold in the original bags stating it to be a gift from the USA. It looked and tasted like pig feed. | ||

| Worse though was the fact that usually the needy, starving natives hardly ever saw anything from such donations. An American we met in Benin told us of having witnessed the police beating with sticks and chasing away the hungry people who'd come to a deposit of donated grain and. Corruption may well be Africa's biggest problem and the worst enemy of its peoples' well-being. | ||

| The changing vegetation made us happy for our camels as well, they'd love to eat juicy greenery instead of stale dry straw. At least that's what we assumed. | ||

| To our great surprise, the animals didn't share our exultation. When led to trees covered in tender green leaves, they ignored them and instead searched for bits of dry grass on the ground. No matter how much we coaxed and wooed, they steadfastly refused to eat anything green. Slowly it dawned on us: Both camels were about six years old, and the drought was in its seventh year. That meant they had never before encountered green fodder. | ||

|

||

maybe if we'd have shown this picture to our

camels.....; photo: web |

||

| In the end, X had to climb some trees and cut armfuls of tender leafy twigs, which he consequently force-fed to the camels by pushing handfuls of leaves down their throat while I was holding their mouths open. This wasn't agreeable to the beasts at all, they did a lot of blowing up their tongues, gurgling and growling, inter spaced with some mean biting attempts. | ||

|

||

| Water was less scarce now too, which was great. As villages became more numerous, there still were some that hadn't seen rain for several years, but more and more wells we passed were well filled. | ||

| Despite water being sufficiently available, often we weren't allowed to make use of a village well without having to pay in tobacco, tea or sugar or a few bills of CFA first. At other hamlets, we encountered helpful and friendly people. | ||

| (Haram is an Arabic word, used in the Qu'ran for that which is forbidden. A similar concept to immoral, Haram also has the meaning of unclean, that which will defile a person. Consequently to steal or rip off people is haram; a thief is often called a harami.) | ||

| It being too late to ride on, we made camp just outside the village. We hardly had made ourselves comfortable when the village chief appeared with a huge bowl full of boiled round little nuts that grew abundantly on hundreds of bushes in the area, topped by a few spoonfuls of maize. Neither cooked nor raw did those nuts taste any good. Neverless, of course we bade the chief to sit and shared our last tea and sugar with him. | ||

| All we had left now were a mere 300 CFA, which had to last us until Niamey. | ||

|

||

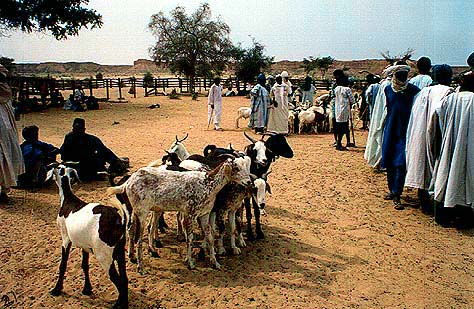

cattle market at Filinge; photo: web |

||

| The camels by then were so weak that whenever one of the roadside trees threw its shade unto our path, they'd just let themselves drop to the ground. With the distance between two trees only being a few meters, our progress was slow and laborious indeed. Since Filinge mileposts announced the number of kilometers still separating us from Niamey. | ||

| Due to the camel's bad state of health, we had to slow down our pace and weren't able to ride for the customary daily lengths of time anymore. | ||

| Two days after leaving Filinge, at dusk we stopped at another small hamlet possessing a water hole. A one-legged old man in rags offered us some watery millet drink, which we gratefully accepted. Having fallen asleep with empty stomachs, the same man woke us a while later; he'd come with a plate of sandy maize and some good milk. In the morning we had some more millet brew. We were extremely grateful for having met such a generous person. | ||

| As we were down to 100 CFA, we couldn't afford to buy food. The animals weren't any less hungry, they still hadn't gotten used to eating greenery and had to be force fed. | ||

| Worn out and exhausted we finally reached Niamey, an uninspiring town we took an immediate dislike to. | ||

|

||

back to main index |

||