|

if your browser doesn't support the menu, please use the links at the

bottom of the pages

|

||

|

||

the Benin coast in fine weather; photo:web |

||

| About a kilometer down that path we arrived at a tiny hamlet of straw huts in varying states of decay, populated by a handful of Christian, as they pointed out to us, fishermen and their families. Unfriendly and only interested in the possibility of earning a few CFA, they agreed to let us a solitary hut down at the beach, consisting of four walls and a roof built of frayed palm fronds, set directly on the sand. After a bit of haggling, we managed to half the rather steep sum the natives initially had asked for and paid our rent for one month in advance. | ||

| The fishermen's village was situated on a clearing in the woods, away from the beach and invisible from our new residence. In the back of our hut, extending for several kilometers along the coast in both directions, stood rows upon rows of coconut palms. | ||

| The ocean, less than a hundred feet from out shack, looked pretty rough, angry waves continuously beating on the shore with great force and much clamor. Soon the sun glided into the sea, plunging us into a moonless night only faintly lit by the thousands of stars spread out on the velvety sky, glittering like diamonds under a jeweler's lamp. Beating at the mosquitoes on our arms, legs and faces, we made a few mental notes of things we'd have to buy next day, candles being among the foremost, and soon curled up on our mats. | ||

| Sleep was impossible though. The air was thick with mosquitoes, and the pieces of clothing we used to cover ourselves and hide under didn't help a bit. After a while of restless turning and cursing, we decided to sleep right at the beach, hoping the wind would keep our tormentors at bay. | ||

| Snatching up our mats, we descended to a spot near the shore, but as soon as we'd lain down again, at least a dozen of mosquitoes settled once more on every inch of our skin. | ||

| Early the following morning, exhausted and bleary eyed from a sleepless night ......by the banging of the waves and the sharp humming of the mosquitoes, we crept back to our hut to finally find a few hours of rest. Waking up in mid-morning, we walked up the broad path to the main road and caught a bus to Cotonou. | ||

|

||

| |

||

| Benin has been the location of one of the great medieval African kingdoms called Dahomey. During the 13th century, the indigenous Edo people were run by a group of local chieftains, but by the 15th century a single ruler known as the 'oba' had asserted control. Under the dynasty established by Ewuare the Great, the most famous of the obas, Benin's territory expanded to cover a region between the Niger River delta and what is now the Nigerian city of Lagos. The obas brought great prosperity and a highly organized state to Benin. They also established good relations and an extensive slave trade with the Portuguese and Dutch who arrived from the 15th century onwards. | ||

| The decline of the obas began in the 18th century when a series of internal power struggles began, which lasted into the 19th century, paving the way for the French takeover and colonization of the country in 1872. In 1904, the territory was incorporated into French West Africa as Dahomey. | ||

| While Porto-Novo is the official capital; Cotonou is Benin's seat of

government and main port town. |

||

|

||

Cotonou market; photo: web |

||

| Benin seemed to be somewhat less poor than Niger, with sufficient food available, much of it imported. Palatable street food was available for 5 CFA. | ||

|

||

| The local staple was a mush made either of cornmeal or of gari, dried and grated manioc. In Brazil, many years later, I was to encounter the same manioc puree under the name of pirão.It's quite delicious, and I still prepare it once in a while. In Benin it is prepared with water only and takes its flavor from the meat or fish sauce it is eaten with, while in Brazil it is usually yellowish and flavored, as it is often prepared with the sauce of muquecas, the Bahian fish stews. | ||

| Vegetables were scarce and expensive; a kilo of potatoes cost 100 CFA, one of cabbage even 700 CFA, equivalent at that time to approximately 1 US$, which in the early seventies was worth at least double of what it is now. For Africa such prices were exorbitant. | ||

| We had sampled some very delicious mangoes in Niamey, huge fruits of superior quality and taste, their flesh firm without being in the least stringy. We'd also been told those wonderful fruits would be available abundantly down in Benin as well, and had been looking forwards to gorge ourselves on them. Now, to our great disappointment, we learned that the mango season was over, having ended the previous month. | ||

Back "home" we gathered a heap of dried

palm fronds, not too difficult an undertaking given the fact that our

hut stood at the edge of a huge coconut plantation. The frond's stems

and the boat shaped, woody bracts made for ideal cooking fuel, while

the fibrous sheath material were perfect to start the fire with. |

||

|

||

the perfect fuel; photo: web |

||

| With the passing weeks, we had to foray ever farther into the plantation for dried palm leaves, as slowly we burned up all the material in our nearer proximity. | ||

|

||

sea side coconut plantation, Benin; photo:

web |

||

| Alas, the protection our mosquito net afforded us unfortunately was much less than hoped for. First of all, the net was tiny, actually too small for two persons. Scores of mosquitoes settled on its outside surface, eagerly pushing their stings through the netting, ready to sting us whenever our skin touched the fabric. | ||

| Still, we felt considerably better than the night before, and went to sleep with the hope of undisturbed night. The first few hours we did indeed sleep quite well, but long before dawn we woke up with our skins covered by mosquito bites once more. The rest of the night passed as the one before, turning and scratching ourselves. As soon as it dawned, the reason for our suffering was evident: The cheap net we had purchased was made of very brittle second hand fabric; it ripped whenever, turning in our sleep, we got its hem caught underneath our bodies. | ||

| Pretty soon a daily routine developed: Every morning I could be seen sewing new patches of bits of printed cotton onto the fresh rips, every night the net got damaged further, until in the end there wasn't much of its original tissue left. | ||

|

||

African orange-tailed Agame lizard; photo: web |

||

| We didn't live alone on our beach. Apart from the family of huge multicolored lizards residing in our hut, thousands of small crabs shared the vicinity with us; they'd scurry about in their funny sidewise way and quickly disappear into their holes in the sand. Sometimes one of those tiny fellows would loose its way and climb up the side of our mosquito net, walk over its top and down again the other side. | ||

|

||

| Even for washing the dishes the ocean was too wild. More than once a calabash spoon or a plate was snatched right out of my hand by a wave and gone immediately. To top it, the sand was polluted by small lumps of thick black oil that stuck to the soles of our feet and were difficult to remove. The big ships we saw passing by evidently used the ocean as a dump for their wastes. | ||

| If all that wasn't enough, the weather was anything but pleasant. In our first weeks we experienced only two really beautiful days; usually the sky was gray and often it rained for days. The humidity crept into all our things. One day we noticed that our erstwhile red passports had turned green with mildew. | ||

|

||

Benin beach during rainy season; photo: web |

||

| The beach photo above shows exactly what we looked upon daily during the long weeks of rain; the colours, the waves, the sand: all a perfect match. This picture indeed gave me a strong flash of "dejà vue". | ||

| Money was running our and our diet consequently was getting poorer by the day, consisting mainly of a gruel made from a greenish type of low quality, sour tasting cornmeal, fit maybe to feed pigs, donated by the USA for the hungry Africans, who got to see it mainly in the shops where it was sold. The manioc gari we alternately prepared hardly tasted any better. Only seldom could we afford some vegetables; even onions were too expensive. | ||

| On one of our shopping forays to Cotonou we came across huge pineapples piled high on a market stall. The fruits were by no means cheap, nothing we could afford really, but our craving for a special treat was strong enough to warrant the decision to indulge ourselves. | ||

| Back at our hut we first ate our customary frugal meal before, our mouths watering with anticipation, we started to cut the first of the pineapples. What the knife revealed though looked much too dark and gave off a sour, over ripe smell. Disappointed, we cut the next one, it too was putrid. Inexperienced as we had been concerning pineapples (in the seventies, fresh pineapples were hardly available in ordinary German or Swiss super markets), we had wasted our money on two worthless, spoilt fruits. | ||

|

||

| During those weeks we were getting desperate enough to jump up whenever we heard a ripe coconut drop, and go in search of it as a welcome addition to our diet. The coconut pieces were hard to digest and gave us bellyache. | ||

| X meanwhile had adopted the habit of chewing Kola nuts, a passion I didn't share; the decidedly bitter taste was lacking in appeal to me. | ||

| Kola nuts, which are thought to represent the body of the creator Mawu, play an important role in Voodoo ceremonies, and there are special customs involving them at weddings and other occasions. The nuts are also used for medicinal purposes. | ||

|

||

| Besides the fact that Kola nuts contain caffeine and act as a stimulant and anti-depressant, they are also thought to reduce fatigue and hunger, aid digestion, and work as an aphrodisiac. Their stimulating effect is similar to that of a strong cup of coffee. | ||

| Our neighbors from the nearby village didn't care about us one way or the other, they asked nothing of us but also never offered any help. Generally people in West Africa seemed to believe that whites never need any help; when in trouble, they only have to enter a bank to replenish their funds. | ||

| This didn't apply to us, so I had to sell my heavy, solid silver Tuareg bangle at a Cotonou silversmith for 5000 CFA to be able to buy some food and a pack of Nivaquine tablets to put a stop to the malaria. A short while after, some money arrived from Germany. | ||

| Some travelers, like most of the Peace Corps volunteers we met, took malaria pills as a prophylactic measure. We didn't see any point in poisoning our system more than was really necessary, even less so after a friend showed us the package insert of his malaria medecine, listing among the side effects the possible loss both of hair and of memory! | ||

| If it felt like we had caught malaria, the symptoms mainly being fever and bodily aches, we swallowed the recommended amount of the pills and felt better pretty soon. Three times during our year in West Africa we contracted the disease, though it seems that it was either one of the less dangerous strains or our immune system was in pretty good shape, as we always got rid of it without any complications. | ||

| The only solution left to resort to was insecticide; something I'd never think of using nowadays because of its toxic qualities, but back then we were young and careless. So we carefully dusted our clothes with great amounts of the white powder we had purchased at a pharmacy. My skirts, being gathered in hundreds of tiny folds at the waist, were an excellent hiding place for lice, consequently each fold had to be treated singly with the insecticide. Despite our using really generous amount of the poisonous powder, it didn't help much; those bloodsuckers were really tough. | ||

| Weeks later, in Timbuktu, we realized that the lice had disappeared. My guess was that the extremely dry, hot climate of Mali had finally finished them off. | ||

| The group consisted of one older man, two younger ones and two chicks. The guys liked the beach and wanted to stay for the weekend, while the girls wanted to leave. The group nevertheless decided to stay for the weekend. Annoyed at not getting their way, the girls did an impressive show of bitching and sulking, one even going as far as to refuse any food for the whole of Sunday. | ||

| As a consequence, the three guys came over to our hut, and we had a good time cooking and eating together, and talk sharing our Africa experiences. | ||

| Only a few days later we encountered a couple of Frenchmen who'd driven down a couple of Peugeot cars from France, for, just about literally, peanuts. Other Westerners, with a few Japanese thrown in for good measure, passed through many West African villages buying up by the kilo all the valuable trading beads they could get their hands on. | ||

| |

||

|

||

The most beautiful of these antique glass beads are

those made in Italy, like the colourful Millefiori (upper picture)

or the blue, red and white patterned Chevron (right above).

Trading beadsin the seventies were pretty much en vogue in

the West, both to be worn as jewelry and as collector's items, accordingly

sold at a good profit. Today, a single Chevron bead in good

condition can cost 200 $ and more. |

||

| . | ||

| With sufficient people to talk to, some pretty good times started. All day long we talked and smoked, together we prepared tasty soups, macaroni with tomato sauce, or rice with fish. Gilbert taught us to prepare a solid, French variety of rice pudding, or "gateau du riz". | ||

| While food was being prepared, nobody was allowed to move. Having nothing resembling a table, all our utensils were placed on the sand covered ground. Because the rubber flip-flops we all wore catapulted a high fountain of sand into the air at every step, the only way to a sand-free diet was to allow nobody to get up until the cooking pot was covered and set on the fire. | ||

| After dinner, we sat conversing long past midnight, or listening to Gilbert's transistor radio for a change. The nights were incredibly beautiful; in a clear sky the full moon's light was so intense it was actually possible to read by it. | ||

| Talking about our mutual traveling adventures for hours and hours, we discovered that Gilbert was the .... of a legend we had heard about a few years earlier, while passing through Afghanistan, more than once. It was a frightening story that had made the rounds among the travelers on the famous "Hippy trail": Two Frenchmen, it was told, who'd camped outside some godforsaken village, had been attacked and killed by aggravated locals. Ostensibly because the two foreigners had chosen some prohibited or probably sacred spot as their sleeping place. | ||

| As it turned out, Gilbert had been one of the two, and while his friend had actually been killed, Gilbert himself had survived, if only barely. His scarred face and body were bearing witness of the attacker's ferocity. | ||

|

||

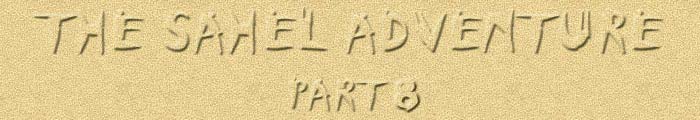

informal Voodoo dance, Benin; photo: web |

||

| It was four kilometers walk to Ekpé, nearest market. If only a few basic items were needed, like fruit or vegetables, we walked there. The market wasn't held at regular intervals though, but announced a day ahead on local radio. We more than once missed it, and had to return empty handed. | ||

| On one of those forays, we happened upon a group of youths, boys and girls both, dressed in strange colourful costumes embellished with cowry shells, dancing in the street to the beat of drums. Their faces were obscured by strings of beads descending from their caps. It was the only time we actually witnessed something resembling a Voodoo ceremony during our time in West Africa. | ||

| Cotonou we liked the least, despite its great market. Anything one could possibly think of was sold there: fabric, household goods, vegetables, meat, fish, musical instruments and much more. There also was a large Voodoo section, where dried animals, tree bark, spices, statues, and amulets were sold. | ||

|

||

market stall selling ingredients for charms

and potions; photo: web |

||

| In Cotonou we bought our grass, at a poorly furnished small apartment; the vendor's home. Usually we sat a while with the young man, to chat and share a smoke. On one of our visits we found him busy fashioning a small talisman from a greasy matter that looked like washing soap, which it probably was. As he explained to us, rubbed on his body, this magic substance was supposed to attract more business. | ||

| We presented him with an amulet to be worn as a protection against the police, of which he was terribly afraid. Not because we thought a talisman would actually keep the police away, but out of hope that it would have the psychological effect of alleviating the youth's exaggerated fears at least to some extent. | ||

| Locals generally seemed to be pretty high strung in Cotonou. Once, when we crossed the main market, people freaked out completely and a real mass hysteria ensued, with the wildly gesticulating market women screaming and shouting like banshees. | ||

| We may not have looked too conventional, X wearing his Afghani shirt embroidered with beads and coins and a turban, me in my usual long skirts and blouse, but in no way frightening, except to a people living in constant fear of witches and sorcerers. When finally an old hag started to scream for the police at the top of her screechy voice, we jumped into the next taxi and made off. | ||

|

||

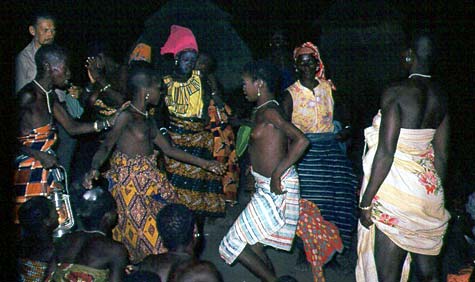

Porto Novo market woman; photo: web |

||

| Porto Novo we liked better, it was a cool town where the market women gaily called "Hallelujah Maria" after us. The place seemed to possess a more relaxed, friendlier atmosphere than Cotonou, but of course this might have been a purely subjective impression. | ||

| Stories of strange events abound - and not all are easily dismissed as being purely anecdotal. Often there were multiple witnesses to the events. | ||

| We were told that if somebody seen by some committing a murder was identified by others as having been somewhere else at the same time, that person would not be convicted. In such a case the crime had probably been committed by a sorcerer, whose magical knowledge enabled him to impersonate someone else. | ||

| Another story we heard was about two convicted witches who, after having been released from jail on competition of their sentence, were awaited by a mob who lynched them on the spot. I've forgotten where this was supposed to have taken place; it might have been Burkina Faso. | ||

|

||

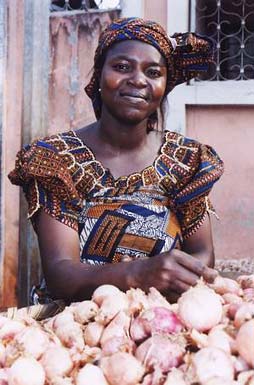

| In its ancient home Benin, Voudon was rather discouraged by the authorities back in the seventies; this seemed to have changed meanwhile. | ||

|

||

Daagbo Hounon Houna, Voudon community leader

in Benin; photo: web |

||

| In 1996, Benin's government inaugurated National Voudon Day, giving the religion practiced by 65 percent of the 5.4 million Beninese an official place alongside Christianity and Islam. | ||

| Thus, right in front of our hut we had marked a small circle in the sand with a border of seashells and placed some small items from various religions inside, a Shiva lingam among them. | ||

| One afternoon Patrick returned from shopping with an angrily shouting cab driver in his wake. The matter of dispute was the outrageous fare the driver insisted on charging, and to lend further weight to his demand, he'd taken possession of Patrick's shopping bag. Suspecting the bag to contain not only edibles, but smokables as well, X tore it out of the man's hands, insisting it belonged to him and not to our French friend. | ||

| The taxi driver was standing in close proximity to our "sacred" space, which couldn't be passed the wrong way round, so X had to nearly step on the angry man's toes to pass him. Further incensed by this, the native started to curse even more, but once we'd managed to explain to him the significance of that circle in the sand, he calmed down and, in conversation with Patrick, walked back towards the dirt path where he'd parked his taxi. | ||

| The two of them had hardly walked a dozen paces when a snake appeared directly in front of the taxi guy. It was Patrick who saw it first and pulled the man back, thus preventing him from stepping on the reptile and getting bitten. | ||

| Eyes bulging with freight, the guy was now convinced that X's magic had called the snake to appear. He refused to believe that X, dressed in wide African trousers, a string of amulets around his neck and wearing his hair in three thick plaits, was an ordinary Swiss citizen and not some adept Voodoo sorcerer. The frightened man suddenly was in very much of a hurry to get away, and now accepted without delay the fare Patrick, knowing the rates very well, had offered to pay in the first place. The poor cab driver stumbled back to his taxi as fast as he could and made off; he must have felt very lucky to have gotten away alive. | ||

| On hearing the same noise once more though, I turned my head around, and within a split second I was on my feet, running and shouting. What had moved right behind me wasn't a lizard, but a tiny, luminously emerald green snake! | ||

| I was to learn later that this little bugger is called a "three minute snake" by the locals, aptly named after the amount of time left to its victims after getting bitten. | ||

| 30 years later, trying to find out more about my pretty green visitor from Internet snake sites, I reached the conclusion that most likely it had been a Green Mamba. If indeed that's what it was, it was just a baby one though. Apart from the size, everything else fits: Green Mambas are found in Benin, they like costal and humid regions, they are, of course, green :), they eat small animals like the lizards living in our hut, and they are pretty deadly. | ||

|

||

Green Mamba (though definitely not a baby one);

photo: web |

||

| Another letter sent off in Senegal contained disturbing news. Our second friend who, accompanied by his girlfriend, also had planned on meeting us in Timbuktu, was too ill to travel on and had to return to Germany. | ||

| His was a very tragic fate. As a young boy, he had contracted bone cancer in his leg. Due to his parents', who were strict adherents of the sect of Jehovah's Witnesses, refusal to allow the necessary and life saving amputation of their son's leg, the cancer had recurred. | ||

| Our friend was to die at 24, a mere few days before we arrived back in Germany, one and a half years later. | ||

|

||

roadside hairdresser cum food seller; photo:

web |

||

|

||

back to main index |

||