|

if your browser doesn't support the menu, please use the links at the

bottom of the pages

|

||

|

||

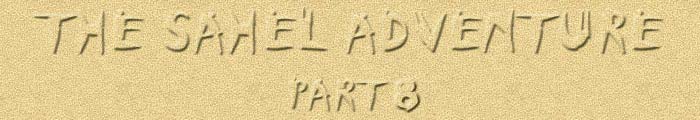

street dancing; photo: web |

||

Ghana certainly was the place we liked

best of all the West African countries we visited. Music was in the

air, and Ghanaians of all ages moved their bodies in rhythm with the

sound. On the streets, in the shops, in restaurants - whenever a mere

fragment of sound hit a pair of ears, butts started to waggle. The atmosphere

was saturated with colours and laughter. Ghanaians also are pretty smart

dressers. For church visits on Sundays, the families really dress up

and parade in all their finery, the women wearing big hats. |

||

|

||

| Much of the modern nation of Ghana was dominated from the late 17th through the late 19th century by a state known as Asante or Ashanti. In the matrilineal Asante society, descent is reckoned principally from mothers to children. It is therefore crucial that women bear females, who will continue their line. | ||

| Asante was the largest and most powerful of a series of states formed in the forest region of southern Ghana by people known as the Akan. Akan entrepreneurs used gold to purchase slaves from both African and European traders. Indeed, while Europeans would eventually send 20 - 40 million slaves to the Americas, the Akan became initially became involved in slave trading by selling African slaves to African purchasers. | ||

| The Portuguese, who came to Ghana in the 15th century, found so much gold between the rivers Ankobra and the Volta that they named the place Mina - meaning Mine. The name Gold Coast was later adopted to by the English colonizers. | ||

| In 1482, the Portuguese built a castle in Elmina. Their

aim was to trade in gold, ivory and slaves. In 1598 the Dutch joined them,

capturing the Elmina castle from the Portuguese in 1642. English, Danes

and Swedish traders arrived by the mid 18th century and dotted the coastline

with their forts. By the latter part of 19th century the Dutch and the

British were the only traders left. When the Dutch withdrew in 1874, Britain

made the Gold Coast a crown colony. |

||

| Ghana gained its independence in 1957 as the first African country south of the Sahara to get rid of colonial rule. | ||

|

||

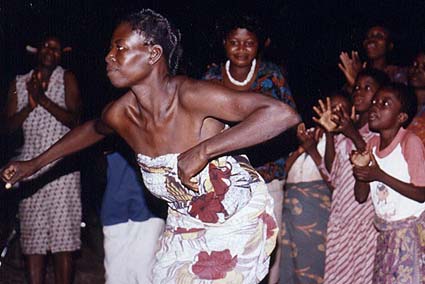

Ghana’s Ashanti King Otumfuo

Osei Tutu II; photo: web |

||

|

||

|

||

| Apart from a few minor details of attire (the Americans sporting baseball caps, while the Canadians preferred white, rimmed baby hats), most hostel residents had one thing in common: they spent their evenings, and often the bigger part of their days as well, smoking and drinking on the public terrace. And they couldn't hold their liquor. | ||

| Seeing them staggering around, falling down and getting up only to collapse again after one or two steps, and listening to their incoherent babble was like watching some crazy movie. We thought the spectacle amusing for a while, but soon started to feel pretty much annoyed. The only time the place turned quiet for about an hour was when everybody left for dinner. After returning, the carousing continued for the greater part of the night. | ||

| Local booze had a telling name: Akpeteshie, which, according to what we were told, means "Kill me quick". Rumor had it that Omo washing powder was among the ingredients making up the potent brew! | ||

|

||

| Annoyed with all the boozing and continuous racket, our Austrian friend didn't get tired of hurling strings of insults in his Austrian German dialect at the incomprehensive Americans. After staying in Accra for three full months, he suddenly decided he'd had it, bought himself a plane ticket to London and bade us farewell |

||

| Other friends we made at the hostel were a Brit by the illustrious and unforgettable name of Francis Drake and his girlfriend Lynn. Francis was cultured and pretty well read, a welcome opportunity for some good discussions. He also knew and told us a few facts about trading beads. | ||

| As to local friends, we only found one in all those weeks in Ghana, a Muslim in his thirties, who was genuinely interested in making our acquaintance only and not in receiving gifts. We visited him several times at his home for tea and a chat. The fact that Ghanaians spoke English rather than French once more facilitated communication a lot. X for one didn't speak any French, so it had always been up to me to translate for him in the erstwhile French colonies. | ||

|

||

| But even the way grass was smoked in West Africa didn't appeal to us. Unlike in the oriental countries, where smoking cannabis always involves certain rituals and customs, and the pipe, chillum or joint is invariably shared with everybody present, in Accra a dude would enter the room, sit down, roll his fatty using a piece of newspaper instead of cigarette paper, and smoke it all by himself, or just maybe offer it to a friend for a puff or two. . | ||

| If we didn't hang out at the hostel, we spent our time going for walks either in its neighborhood or downtown, watching the locals getting on with their lives and doing our shopping. I vividly remember an embarrassing little incident from one of those days: Coming from the market with my shopping, proudly balancing my big shopping basket on my head, I stumbled badly due to the uneven pavement. The basket flew from my head, scattering its contents all over the ground. What a blow to my vanity! :) | ||

| Carrying stuff on your head is very convenient, especially if it's something really heavy like a suitcase or a case of beer, but it has one drawback: it's difficult to see the ground at your feet. | ||

|

||

|

||

| Market women are generally in control of their economy, they are most concerned about attaining a better life for their children, but they still consider being married the ultimate in spite of their economic independence. |

||

| African women are engaged in caring services, looking after children aged parents, in-laws and others. They are often involved in farming and other agricultural activities. They fetch water and cut firewood for fuel, cook and take food to the men on the farm and carry back produce for the market and domestic consumption. In many instances, they are responsible for fulfilling the food needs of their children. | ||

|

||

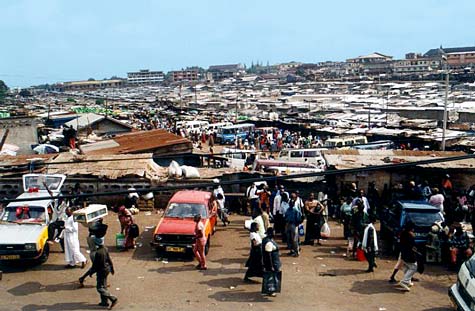

Accra market; photo: web |

||

| Karate movies were popular among the locals, popular enough to necessitate banning them somewhere in the vicinity, I'm not sure if it was in Ghana or a neighboring country, as kids would imitate the movie heroes by poking fingers into each others eyes. | ||

|

||

| Neither did they like their skin colour. In Accra, numerous

billboards touted bleaching powder for lightening people's skin tone.

The "black is beautiful" philosophy of their American brothers

and sisters evidently hadn't reached the ancestral continent yet. In the

words of an Ghanaian journalist: Historical factors can account for

this dangerous and unhealthy perception we have of ourselves as dark-skinned

people. Our desire to change our skin colour can only be explained by

our feeling of low esteem which is a direct result of our colonial experiences. |

||

Many bleaching remedies contain questionable substances

as arbutine, corticosteriods and the carcinogen hydroquinone.

Long term use of such creams and lotions have disfigured thousands of

black African women . |

||

Today those harmful bleaching creams

are banned in Ghana, nevertheless, they are still in demand and can

easily be found. |

||

| Bleaching creams were first pushed on the market in the United States for African-American women who were encouraged to keep their skins lightened in an effort to emulate the Caucasian woman, who was put on a pedestal as the ultimate measure of human beauty. Later, the market was expanded to apartheid South Africa and then onwards to East Africa till eventually it ended up in West Africa where it has taken root. | ||

|

||

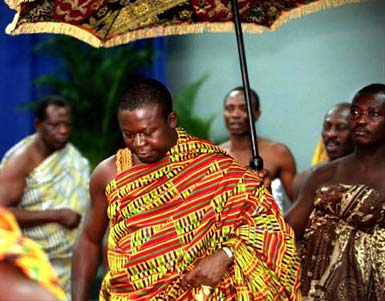

| In their desire to be modern and to emulate the culture of the whites, thousands of African mothers would abandon breast feeding in favor of Néstle milk formula. It was a great problem in the seventies and still is one today. | ||

|

||

African Nestlé ad; photo:

web |

||

| The water mixed with baby milk powder in poor conditions is often unsafe. This leads to diarrhea and often death. Baby milk also is very expensive, it can cost over 50% of a family income. As a consequence, poor people have to over-dilute the baby formula to make it last longer. Babies are then likely to become malnourished. 4000 babies die each day from unsafe bottle feeding, say UNICEF. | ||

| Even undernourished mothers can breast feed. Without breast feeding, babies don't get the benefit of passive immunity normally passed on in the mothers' milk. Breast-feeding is free, safe and protects against infection, without doubt it is the best start in life for a child - but Néstle's baby food marketing puts profits before lives. | ||

|

||

| Eating from banana leaves is quite common in different cultures; we were acquainted with the custom from from South Indian or Sri Lankan restaurants and had always thought it very convenient. Yet in India, people are very much concerned with food hygiene (even if in a way not fathomable for outsiders), so it would be unthinkable not to throw away the leaves after use. Sometimes cows were eagerly awaiting the discarded "plates" in the restaurants' backyards, where each customer went to dispose of his leaf. | ||

| Seeing used leaves being washed for re-use to our eyes was a shocking sight. | ||

|

||

Ghana barber shop sign; photo:web |

||

| A source of both amazement and amusement were the colourful barber shop signs, depicting a catalog of intricate women's hair braiding patterns or the latest in men's hair styles. The "shops" themselves at times consisted of barely more than a chair set up in the open and a signboard hanging from a tree or market stall. It was fascinating to watch the hairdressers doing their job, laughing and joking with their customers while tying plastic wire tightly around single strands of hair to make them stand out like spikes or antenna. | ||

|

||

| This also proofed as an easy way to settle old scores or get rid of a rival. A guy only had to clutch his nether regions, shout "It's gone" and point out the alleged sorcerer, who'd get lynched on the spot by the worked up masses. | ||

| The situation got worse by the day until one of Accra's biggest newspapers published an article divulging the protective measures to be taken against those "genital snatchers": To carry some salt and pepper in one's pockets! | ||

| Another outbreak of the same mass hysteria was to happen again in Ghana in 1997; with at least seven alleged penis snatchers getting beaten to death by angry mobs. Such "vanishing genitals" stories abound in various West African countries, where belief in sorcery is common and widespread. | ||

|

||

| A similar if technically more advanced panic is spreading these days in Nigeria, and I'm sure the neighboring West African countries will also get affected, if they not already are. People receive SMS messages warning them not to answer calls to their mobiles sent from certain numbers, as that would mean instant death. | ||

| Still today though, I decline the use of forks except for salads or spaghetti, and invariably ask for a spoon if I'm not given one right away. Forks are hardly useful for eating purposes, and the way people in the West customarily eat, brandishing the fork in one hand and the knife in the nother, looks hilariously ridiculous in my opinion! I never was one to do something in a certain way just because that is the established way of doing it, I've kept me an open mind and do things the way I see fit. But I'm disgressing........:) | ||

|

||

| At road junctions hawkers sold cheap snacks like Kofi Brokeman: Fried plantains with peanuts, aptly named because affordable even to the poor. Corn cobs, freshly roasted over charcoal, also make a nice snack. Kofi by the way is a very common first name in Ghana, it is a name given to boys born on a Friday. Children are often named by the weekday they are born on, a girl born on a Tuesday thus could be called Abena. | ||

| On that unforgettable occasion, we were maybe two thirds through our plates when two young men passed by, each balancing a huge, heavy-looking barrel on his head. Suddenly one of them stumbled and his barrel crashed to the ground, spilling its contents on the sidewalk and splashing the restaurant customers at the nearest tables. | ||

| Within a few second a great commotion arose, with people jumping up screeching and cursing and running off in all directions. An evil smell spreading from the barrel's spilled contents left no room for doubt about the nature of the substance: It was human body wastes or, in plain language, a load of shit. | ||

| Luckily, we sat too far away from the spot where the accident happened to suffer more damage than a few drops of spillage on the hem of my dress. Still, there was no thought of finishing our meal. Half a minute after the mishap, all the tables and benches were completely deserted except for the enraged owner of the place, who stood amidst her cauldrons, screaming and heaping insults on the poor lad who'd caused her such devastating loss of business. | ||

|

||

| Returning to the hostel after dinner we had made it a habit to stop at the tiny streetside table of two young women selling small pieces of chocolate. One night we had no change left in our pockets and asked the vendors, who knew us very well from buying of their chocolate as a daily ritual, if we couldn't pay for our dessert on the following day. Fat chance! "You people never pay!" one of the girls decidedly exclaimed and sent us off without our customary treat. | ||

| There was too much we couldn't fathom: Why, when I'd give a few coins to a destitute beggar, would a well groomed fat man clad in an expensive suit approach me and extend his hand for alms as well? Why would complete strangers ask us for presents? How could people debase themselves by walking up to us to brush off a bit of imaginary or real dust from our clothes and ask for a tip? | ||

| Poverty couldn't be the sole answer; we had spent much time among poor people in places like Afghanistan, Pakistan or India, but never encountered anything resembling such a high level of general greed. | ||

| An incident on the drive up north confirmed our suspicion that such unpleasant avarice hadn't anything to do with the fact that we were foreigners; rather greed was common among the natives themselves. Traveling by minibus, at a bus stop we were awaited by a group of women and girls selling great, round, dark-red loaves of local cheese. Quite a few of our fellow passengers reached out for those cheeses through the bus windows, handled, felt and smelled them and discussed their merits for a great length of time. | ||

| Finally, the bus driver reared up his engine and the vehicle began to move, yet the prospective buyers still didn't make a move of either paying for the cheese loaves or returning them. Only when the bus gathered speed, the hapless cheese sellers running after it shouting and crying, would the passengers, amid great merriment, throw a few small coins out onto the road. While the desperate cries and subsequent curses of the cheated women grew fainter and fainter, we had to watch the gloating and high spirits of those thieving bastards for the rest of the afternoon. | ||

|

||

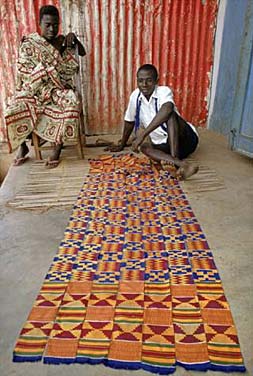

Kente is an Asante ceremonial cloth hand-woven

on a horizontal treadle loom. Strips measuring about 4 inches wide are

sewn together into larger pieces of cloths. Cloths come in various colors,

sizes and designs and are worn during very important social and religious

occasions. In a total cultural context, kente is more important than

just a cloth. It is a visual representation of history, philosophy,

ethics, oral literature, moral values, social code of conduct, religious

beliefs, political thought and aesthetic principles. |

||

|

||

kente cloth; photo: web |

||

| Legend has it that one day during the reign of Oti Akenten (about 1600 AD) two brothers, Nana Kragu and Nana Ameyaw, went hunting in the rain forest. After searching all day for food with no success, they finally spotted a herd of impala. | ||

| They were delighted with their find, but on closer inspection the brothers spied something else, something that hovered near this herd. What was this thing that glistened with the evening mist and reflected the colors of the rainbow? And who was this creature that was sitting in the very center of this delicate object? "I am a spider—I am Anansi, the spider and this 'object' is a web," was the reply. "And in return for several favors I will teach you how to weave lovely webs like this." | ||

|

||

proud weaver displaying his craft;

photo: web |

||

| The term kente has its roots in the word kenten which means "basket". The first kente weavers used raffia fibers to weave cloths that looked like kenten and thus were referred to as kenten ntoma; meaning "basket cloth". | ||

| Traditionally, kente is mainly woven by the Asante and the Ewe tribes of Ghana. The Asante kente is woven in villages just outside Kumasi in the area around Bonwire and Ntonso. | ||

|

||

Kumasi bus terminal; photo:web |

||

Kumasi was our last stop in Ghana. Our minds set on

the fabled city of Timbuktu, we continued by bus in the direction of

the border to Upper Volta, as Burkina Faso was still called at that

time. |

||

|

||

back to main index |

||