|

if your browser doesn't support the menu, please use the links at the

bottom of the pages

|

||

|

||

Niamey; photo:web |

||

| We were more lucky, though the expected letters from our friends weren't at the Post Office, there was at least some money. Not only could we now indulge our appetite for some good food, but also buy a few other necessities. | ||

|

||

our new accommodations |

||

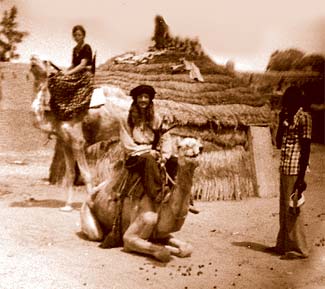

| The camels had been in pretty bad shape on our arrival, and as we now had a bit of cash, we took them to a vet who prescribed daily shots of calcium and vitamin C. To reach the veterinary clinic we had to ride across town; a novel experience in a bustling city with high rises, traffic lights, cars and buses. | ||

| My camel, probably in a similar dreamy mood as myself, had taken a misstep on the cracked dry mud and as it stumbled and its leg folded, my feet had lost their hold on its neck. Luckily, the worst was the shock of finding myself suddenly looking up at my animal from a very unfamiliar perspective; the only thing actually shattered was my pride. Although my bones hurt for a day or two, nothing was broken. | ||

| The cops asked us, not very politely, to accompany them to the police station. Rather nervous and not knowing what to expect, we tied up our camels and went along to the commissioner's office, where it transpired that we were thought to be Tuareg escapees from one of the refugee camps. | ||

|

||

Niamey street scene; photo: web |

||

| That obvious error cleared up, the police chief, a stocky, arrogant fellow, still wanted to keep us at the station for the night, a prospect we didn't fancy and consequently did our best to talk him out of. In possession of our promise to turn up again at seven next morning, he reluctantly let us go. | ||

| Early the next day, after we had waited for an hour and a half for the superintendent's appearance, we were brought downtown to the head offices of the Surreté. There we came to know that the police chief was planning to expel us from Niger. | ||

| After some discussion we were allowed to consult with our country's representative and to return to the Surreté at ten the same morning. By taxi we found Switzerland's representative, a local bank director, who made a call back to the Surreté, where we also returned immediately, only to be informed we were to come back once more in the afternoon. Exasperated, we did as told. | ||

| In the afternoon the police chief told us that due to our camel's conditions and the fact that we were waiting for money, he'd allow us to stay at his own responsibility, but advised us not to be too visible around town. | ||

| Thank heavens I had thought of sneaking in to hide the grass, who knows what would have happened otherwise. Without enough money for a fat bribe, we'd probably have ended up in real trouble. | ||

| From the police agent we also got news from old friends, the French couple we'd traveled together on the date truck from southern Algeria to Ingal, who, as he said, had stood at his place: | ||

| Niger had gained full independence in 1960, and Hamani Diori was elected president unopposed. With some help from a sympathetic French administration, he remained in political power for 14 years. When food stockpiles were found in the homes of Diori's ministers during the drought, it marked the end of Diori's rule. A bloody coup ensued and in April 1974, Senyi Kountché, a military officer, was put in the driver's seat. | ||

| The political change brought a new chief of police, who thought it necessary to throw his weight around and to impress the new government. That he chose to pick on Niamey's foreigners for his show of resolve was just our bad luck. | ||

| |

||

|

||

traffic on Kennedy bridge; photo: web |

||

| To our dismay, in Niamey we learned that further south the climate wasn't suitable at all for our animals; they would invariably perish within a few weeks. That was bad news indeed, and after being told how, if one indeed made it down to the coastal region with a camel, one could put the animal in a tent and charge spectators not only to look at it and touch it, but make additional profits selling dried camel droppings, we were convinced. | ||

| The prospects of having to part with our animals didn't help to improve our mood. With heavy hearts, knowing that our camels wouldn't survive the journey down south and warned that the police could kick us out any day, which would mean loosing our mounts anyway, we decided to sell them, leave Niamey as fast as possible and continue our trip by local transport. | ||

|

||

|

||

| X returned from the camel market with a paltry 35'000 CFA, only half of what we had paid for our animals back at Ingal. Not only was Niamey not affected by the drought that had forced prices for camels to rise in the Sahel region, but the animals also weren't in much demand in a modern city. Worse, and to my great dismay, I learned that camels were sold and bought in Niamey solely for their meat value. We felt terrible for having led our camels that far only to end up at the butchers | ||

| . | ||

| My foot looked worse the next day, so with the help of a wooden stick and leaning heavily on X, I paid a visit to a nearby a dispensary run by the "Red Crescent", the Islamic equivalent of the Red Cross. My wound got examined and I received three horrible shots deep into the soles of my foot. It was the worst injections I ever had, it hurt badly and I'll never forget the noise of the needle piercing the hard flesh. At least that's how I remember the shots, if there really had been an audible sound or not, I can't be sure, it rather seems a bit strange. | ||

| |

||

| Before our departure, we checked once more in vain at the Post Office; neither a letter from our friends nor some more money from Germany had arrived. | ||

| On the morning of our departure we happened to run into Joe once more, who'd disappeared a few days back with the 1000 CFA we had given him to get me some pain killers. Of course he couldn't return the money, so we just said good bye and wished him luck. | ||

|

||

river Niger at sunset; photo:web |

||

| Finally the tiny bus, crammed with 30 passengers, made off in a black cloud of smoke. After only a few hours drive, dusk made an end to our marveling at the lush greenery on both sides of the road. We reached the border to Benin late at night, too late for it to be still open. | ||

| This meant we could roll out our straw mats right on the road near the border post and spend the night under the starry night sky, with no need to further deplete our meager funds. | ||

|

||

back to main index |

||